Alloys are usually stronger than pure metals, although they generally offer reduced electrical and thermal conductivity. Strength is the most important criterion by which many structural materials are judged. Therefore, alloys are used for engineering construction. Steel, probably the most common structural metal, is a good example of an alloy. It is an alloy of iron and carbon, with other elements to give it certain desirable properties.

Alloys are usually stronger than pure metals, although they generally offer reduced electrical and thermal conductivity. Strength is the most important criterion by which many structural materials are judged. Therefore, alloys are used for engineering construction. Steel, probably the most common structural metal, is a good example of an alloy. It is an alloy of iron and carbon, with other elements to give it certain desirable properties.

It is sometimes possible for a material to be composed of several solid phases. The strengths of these materials are enhanced by allowing a solid structure to become a form composed of two interspersed phases. When the material in question is an alloy, it is possible to quench the metal from a molten state to form the interspersed phases. The term quenching refers to a heat treatment in which a material is rapidly cooled in water, oil or air to obtain certain material properties, especially hardness. In metallurgy, quenching is most commonly used to harden steel by introducing martensite.

Hardness of Metal Alloys

In materials science, hardness is the ability to withstand surface indentation (localized plastic deformation) and scratching. Hardness is probably the most poorly defined material property because it may indicate resistance to scratching, resistance to abrasion, resistance to indentation or even resistance to shaping or localized plastic deformation. Hardness is important from an engineering standpoint because resistance to wear by either friction or erosion by steam, oil, and water generally increases with hardness.

In materials science, hardness is the ability to withstand surface indentation (localized plastic deformation) and scratching. Hardness is probably the most poorly defined material property because it may indicate resistance to scratching, resistance to abrasion, resistance to indentation or even resistance to shaping or localized plastic deformation. Hardness is important from an engineering standpoint because resistance to wear by either friction or erosion by steam, oil, and water generally increases with hardness.

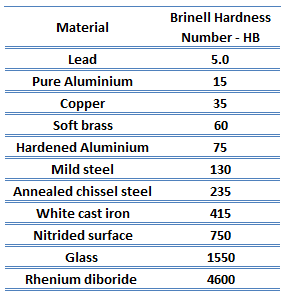

Brinell hardness test is one of indentation hardness tests, that has been developed for hardness testing. In Brinell tests, a hard, spherical indenter is forced under a specific load into the surface of the metal to be tested. The typical test uses a 10 mm (0.39 in) diameter hardened steel ball as an indenter with a 3,000 kgf (29.42 kN; 6,614 lbf) force. The load is maintained constant for a specified time (between 10 and 30 s). For softer materials, a smaller force is used; for harder materials, a tungsten carbide ball is substituted for the steel ball.

The test provides numerical results to quantify the hardness of a material, which is expressed by the Brinell hardness number – HB. The Brinell hardness number is designated by the most commonly used test standards (ASTM E10-14[2] and ISO 6506–1:2005) as HBW (H from hardness, B from brinell and W from the material of the indenter, tungsten (wolfram) carbide). In former standards HB or HBS were used to refer to measurements made with steel indenters.

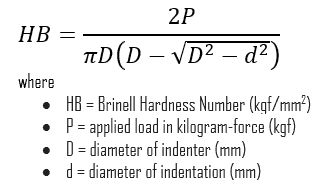

The Brinell hardness number (HB) is the load divided by the surface area of the indentation. The diameter of the impression is measured with a microscope with a superimposed scale. The Brinell hardness number is computed from the equation:

There are a variety of test methods in common use (e.g. Brinell, Knoop, Vickers and Rockwell). There are tables that are available correlating the hardness numbers from the different test methods where correlation is applicable. In all scales, a high hardness number represents a hard metal.

Example – Hardness of Low-carbon Steel

Brinell hardness of low-carbon steel is approximately 120 MPa.

Example – Hardness of High-carbon Steel

Brinell hardness of high-carbon steel is approximately 200 MPa.

Example – Hardness of Damascus Steel

Rockwell hardness of Damascus steel depends on the current type of the steel, but it may be approximately 62-64 HRC Rockwell.

We hope, this article, Hardness of Metal Alloys, helps you. If so, give us a like in the sidebar. Main purpose of this website is to help the public to learn some interesting and important information about materials and their properties.