In metallurgy, stainless steel is a steel alloy with at least 10.5% chromium with or without other alloying elements and a maximum of 1.2% carbon by mass. Stainless steels, also known as inox steels or inox from French inoxydable (inoxidizable), are steel alloys, which are very well known for their corrosion resistance, which increases with increasing chromium content. Corrosion resistance may also be enhanced by nickel and molybdenum additions. The resistance of these metallic alloys to the chemical effects of corrosive agents is based on passivation. For passivation to occur and remain stable, the Fe-Cr alloy must have a minimum chromium content of about 10.5% by weight, above which passivity can occur and below which it is impossible. Chromium can be used as a hardening element and is frequently used with a toughening element such as nickel to produce superior mechanical properties.

In metallurgy, stainless steel is a steel alloy with at least 10.5% chromium with or without other alloying elements and a maximum of 1.2% carbon by mass. Stainless steels, also known as inox steels or inox from French inoxydable (inoxidizable), are steel alloys, which are very well known for their corrosion resistance, which increases with increasing chromium content. Corrosion resistance may also be enhanced by nickel and molybdenum additions. The resistance of these metallic alloys to the chemical effects of corrosive agents is based on passivation. For passivation to occur and remain stable, the Fe-Cr alloy must have a minimum chromium content of about 10.5% by weight, above which passivity can occur and below which it is impossible. Chromium can be used as a hardening element and is frequently used with a toughening element such as nickel to produce superior mechanical properties.

Hardened Stainless Steels

Martensitic Stainless Steels

Martensitic stainless steels are similar to ferritic steels in being based on chromium but have higher carbon levels up as high as 1%. They are sometimes classified as low-carbon and high-carbon martensitic stainless steels. They contain 12 to 14% chromium, 0.2 to 1% molybdenum, and no significant amount of nickel. Higher amounts of carbon allows them to be hardened and tempered much like carbon and low-alloy steels. They have moderate corrosion resistance, but are considered hard, strong, slightly brittle. They are magnetic and they can be nondestructively tested using the magnetic particle inspection method, unlike austenitic stainless steel. A common martensitic stainless is AISI 440C, which contains 16 to 18% chromium and 0.95 to 1.2% carbon. Grade 440C stainless steel is used in the following applications: gage blocks, cutlery, ball bearings and races, molds and dies, knives. As was written, martensitic stainless steels can be hardened and tempered through multiple ways of aging/heat treatment: The metallurgical mechanisms responsible for the martensitic transformations that take place in these stainless alloys during austenitizing and quenching are essentially the same as those that are used to harden lower-alloy-content carbon and alloy steels.

PH Stainless Steels

PH stainless steels (precipitation-hardening) contain around 17% chromium and 4% nickel. These steels can develop very high strength through additions of aluminum, titanium, niobium, vanadium, and/or nitrogen, which form coherent intermetallic precipitates during a heat treatment process referred to as heat aging. As the coherent precipitates form throughout the microstructure, they strain the crystalline lattice and impede the movement of dislocations, or defects in a crystal’s lattice. Since dislocations are often the dominant carriers of plasticity, this serves to harden the material. For example, precipitation-hardened stainless steel 17-4 PH (AISI 630) have an initial microstructure of austenite or martensite. Austenitic grades are converted to martensitic grades through heat treatment (e.g. throung heat treatment at about 1040 °C followed by quenching) before precipitation hardening can be done. Subsequent ageing treatment at about 475 °C precipitates Nb and Cu-rich phases that increase the strength up to above 1000 MPa yield strength. Unlike austenitic alloys, however, heat treatment strengthens PH steels to levels higher than martensitic alloys. Precipitation-hardening stainless steels are designated by the AISI 600-series. Of all of the available stainless grades, they generally offer the greatest combination of high strength coupled with excellent toughness and corrosion resistance. They are as corrosion resistant as austenitic grades. Common uses are in the aerospace and some other high-technology industries.

Hardness of Stainless Steels

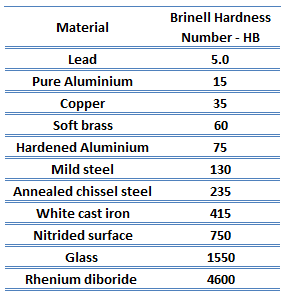

Brinell hardness of stainless steel – type 304 is approximately 201 MPa.

Brinell hardness of ferritic stainless steel – Grade 430 is approximately 180 MPa.

Brinell hardness of martensitic stainless steel – Grade 440C is approximately 270 MPa.

Brinell hardness of duplex stainless steels – SAF 2205 is approximately 217 MPa.

Brinell hardness of precipitation hardening steels – 17-4PH stainless steel is approximately 353 MPa.

In materials science, hardness is the ability to withstand surface indentation (localized plastic deformation) and scratching. Hardness is probably the most poorly defined material property because it may indicate resistance to scratching, resistance to abrasion, resistance to indentation or even resistance to shaping or localized plastic deformation. Hardness is important from an engineering standpoint because resistance to wear by either friction or erosion by steam, oil, and water generally increases with hardness.

In materials science, hardness is the ability to withstand surface indentation (localized plastic deformation) and scratching. Hardness is probably the most poorly defined material property because it may indicate resistance to scratching, resistance to abrasion, resistance to indentation or even resistance to shaping or localized plastic deformation. Hardness is important from an engineering standpoint because resistance to wear by either friction or erosion by steam, oil, and water generally increases with hardness.

Brinell hardness test is one of indentation hardness tests, that has been developed for hardness testing. In Brinell tests, a hard, spherical indenter is forced under a specific load into the surface of the metal to be tested. The typical test uses a 10 mm (0.39 in) diameter hardened steel ball as an indenter with a 3,000 kgf (29.42 kN; 6,614 lbf) force. The load is maintained constant for a specified time (between 10 and 30 s). For softer materials, a smaller force is used; for harder materials, a tungsten carbide ball is substituted for the steel ball.

The test provides numerical results to quantify the hardness of a material, which is expressed by the Brinell hardness number – HB. The Brinell hardness number is designated by the most commonly used test standards (ASTM E10-14[2] and ISO 6506–1:2005) as HBW (H from hardness, B from brinell and W from the material of the indenter, tungsten (wolfram) carbide). In former standards HB or HBS were used to refer to measurements made with steel indenters.

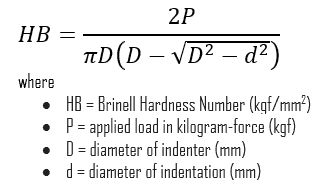

The Brinell hardness number (HB) is the load divided by the surface area of the indentation. The diameter of the impression is measured with a microscope with a superimposed scale. The Brinell hardness number is computed from the equation:

There are a variety of test methods in common use (e.g. Brinell, Knoop, Vickers and Rockwell). There are tables that are available correlating the hardness numbers from the different test methods where correlation is applicable. In all scales, a high hardness number represents a hard metal.

We hope, this article, Hardness of Stainless Steels, helps you. If so, give us a like in the sidebar. Main purpose of this website is to help the public to learn some interesting and important information about materials and their properties.