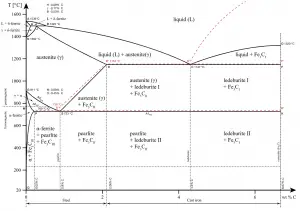

The simplest ferrous alloys are known as steels and they consist of iron (Fe) alloyed with carbon (C) (about 0.1% to 1%, depending on type). Adding a small amount of non-metallic carbon to iron trades its great ductility for the greater strength. Due to its very-high strength, but still substantial toughness, and its ability to be greatly altered by heat treatment, steel is one of the most useful and common ferrous alloy in modern use. The carbon content of steel is between 0.002% and 2.14% by weight for plain iron–carbon alloys. These values vary depending on alloying elements such as manganese, chromium, nickel, tungsten, and so on. In contrast, cast iron does undergo eutectic reaction.

Steel

Steels are iron–carbon alloys that may contain appreciable concentrations of other alloying elements. Adding a small amount of non-metallic carbon to iron trades its great ductility for the greater strength. Due to its very-high strength, but still substantial toughness, and its ability to be greatly altered by heat treatment, steel is one of the most useful and common ferrous alloy in modern use. There are thousands of alloys that have different compositions and/or heat treatments. The mechanical properties are sensitive to the content of carbon, which is normally less than 1.0 wt%. According ot AISI classification, carbon steel is broken down into four classes based on carbon content:

- Low-carbon Steels. Low-carbon steel, also known as mild steel is now the most common form of steel because its price is relatively low while it provides material properties that are acceptable for many applications. Low-carbon steel contains approximately 0.05–0.25% carbon making it malleable and ductile. Mild steel has a relatively low tensile strength, but it is cheap and easy to form; surface hardness can be increased through carburizing.

-

Medium-carbon steel is mostly used in the production of machine components, shafts, axles, gears, crankshafts, coupling and forgings, could also be used in rails and railway wheels and other machine parts and high-strength structural components calling for a combination of high strength, wear resistance, and toughness. Medium-carbon Steels. Medium-carbon steel has approximately 0.3–0.6% carbon content. Balances ductility and strength and has good wear resistance. This grade of steel is mostly used in the production of machine components, shafts, axles, gears, crankshafts, coupling and forgings and could also be used in rails and railway wheels.

- High-carbon Steels. High-carbon steel has approximately 0.60 to 1.00% carbon content. Hardness is higher than the other grades but ductility decreases. High carbon steels could be used for springs, rope wires, hammers, screwdrivers, and wrenches.

- Ultra-high-carbon Steels. Ultra-high-carbon steel has approximately 1.25–2.0% carbon content. Steels that can be tempered to great hardness. This grade of steel could be used for hard steel products, such as truck springs, metal cutting tools and other special purposes like (non-industrial-purpose) knives, axles or punches. Most steels with more than 2.5% carbon content are made using powder metallurgy.

- Alloy Steels. Steel is an alloy of iron and carbon, but the term alloy steel usually only refers to steels that contain other elements— like vanadium, molybdenum, or cobalt—in amounts sufficient to alter the properties of the base steel. In general, alloy steel is steel that is alloyed with a variety of elements in total amounts between 1.0% and 50% by weight to improve its mechanical properties. Alloy steels are broken down into two groups:

- Low-alloy Steels.

- High-alloy Steels.

Cast Iron

In materials engineering, cast irons are a class of ferrous alloys with carbon contents above 2.14 wt%. Typically, cast irons contain from 2.14 wt% to 4.0 wt% carbon and anywhere from 0.5 wt% to 3 wt% of silicon. Iron alloys with lower carbon content are known as steel. The difference is that cast irons can take advantage of eutectic solidification in the binary iron-carbon system. The term eutectic is Greek for “easy or well melting,” and the eutectic point represents the composition on the phase diagram where the lowest melting temperature is achieved. For the iron-carbon system the eutectic point occurs at a composition of 4.26 wt% C and a temperature of 1148°C.

Cast iron, therefore, has a lower melting point (between approximately 1150°C and 1300°C) than traditional steel, which makes it easier to cast than standard steels. Because of its high fluidity when molten, the liquid iron easily fills intricate molds and can form complex shapes. Most applications require very little finishing, so cast irons are used for a wide variety of small parts as well as large ones. It is an ideal material for sand casting into complex shapes such as exhaust manifolds without the need for extensive further machining. Furthermore, some cast irons are very brittle, and casting is the most convenient fabrication technique. Cast irons have become an engineering material with a wide range of applications and are used in pipes, machines and automotive industry parts, such as cylinder heads, cylinder blocks and gearbox cases. It is resistant to damage by oxidation.

The most common cast iron types are:

- Gray cast iron. Gray cast iron is the oldest and most common type of cast iron. Gray cast iron is characterised by its graphitic microstructure, which causes fractures of the material to have a gray appearance. This is due to the presence of graphite in its composition. In gray cast iron the graphite forms as flakes, taking on a three dimensional geometry.

- White cast iron. White cast irons are hard, brittle, and unmachinable, while gray irons with softer graphite are reasonably strong and machinable. A fracture surface of this alloy has a white appearance, and thus it is termed white cast iron.

- Malleable cast iron. Malleable cast iron is white cast iron that has been annealed. Through an annealing heat treatment, the brittle structure as first cast is transformed into the malleable form. Therefore, its composition is very similar to that of white cast iron, with slightly higher amounts of carbon and silicon.

- Ductile cast iron. Ductile iron, also known as nodular iron, is very similar to gray iron in composition, but during solidification the graphite nucleates as spherical particles (nodules) in ductile iron, rather than as flakes. Ductile iron is stronger and more shock resistant than gray iron. In fact, ductile iron has mechanical characteristics approaching those of steel, while it retains high fluidity when molten and lower melting point.

We hope, this article, Steel vs Cast Iron – Comparison, helps you. If so, give us a like in the sidebar. Main purpose of this website is to help the public to learn some interesting and important information about materials and their properties.