The bronzes are a family of copper-based alloys traditionally alloyed with tin, but can refer to alloys of copper and other elements (e.g. aluminum, silicon, and nickel). Bronzes are somewhat stronger than the brasses, yet they still have a high degree of corrosion resistance. Generally they are used when, in addition to corrosion resistance, good tensile properties are required. For example, beryllium copper attains the greatest strength (to 1,400 MPa) of any copper-based alloy.

The bronzes are a family of copper-based alloys traditionally alloyed with tin, but can refer to alloys of copper and other elements (e.g. aluminum, silicon, and nickel). Bronzes are somewhat stronger than the brasses, yet they still have a high degree of corrosion resistance. Generally they are used when, in addition to corrosion resistance, good tensile properties are required. For example, beryllium copper attains the greatest strength (to 1,400 MPa) of any copper-based alloy.

Historically, alloying copper with another metal, for example tin to make bronze, was first practiced about 4000 years after the discovery of copper smelting, and about 2000 years after “natural bronze” had come into general use. An ancient civilization is defined to be in the Bronze Age either by producing bronze by smelting its own copper and alloying with tin, arsenic, or other metals. Bronze, or bronze-like alloys and mixtures, were used for coins over a longer period. is still widely used today for springs, bearings, bushings, automobile transmission pilot bearings, and similar fittings, and is particularly common in the bearings of small electric motors. Brass and bronze are common engineering materials in modern architecture and primarily used for roofing and facade cladding due to their visual appearance.

Strength of Bronzes

In mechanics of materials, the strength of a material is its ability to withstand an applied load without failure or plastic deformation. Strength of materials basically considers the relationship between the external loads applied to a material and the resulting deformation or change in material dimensions. Strength of a material is its ability to withstand this applied load without failure or plastic deformation.

Ultimate Tensile Strength

Ultimate tensile strength of aluminium bronze – UNS C95400 is about 550 MPa.

Ultimate tensile strength of tin bronze – UNS C90500 – gun metal is about 310 MPa.

Ultimate tensile strength of copper beryllium – UNS C17200 is about 1380 MPa.

It must be noted, copper beryllium, also known as berylium bronze, is a copper alloy with 0.5—3% beryllium. Copper beryllium is the hardest and strongest of any copper alloy (UTS up to 1,400 MPa), in the fully heat treated and cold worked condition. It combines high strength with non-magnetic and non-sparking qualities and it is similar in mechanical properties to many high strength alloy steels but, compared to steels, it has better corrosion resistance. It has good thermal conductivity (210 W/m°C) 3-5 times more than tool steel. These high performance alloys have long been used for non-sparking tools in the mining (coal mines), gas and petrochemical industries (oil rigs). Beryllium copper screwdrivers, pliers, wrenches, cold chisels, knives, and hammers are available for these environments. Because of the excellent fatigue resistance, copper beryllium is widely used for springs, spring wire, load cells, and other parts that must retain their shape under cyclic loads.

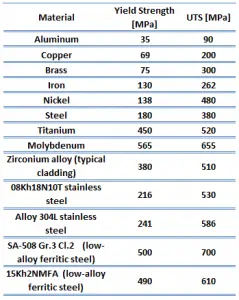

The ultimate tensile strength is the maximum on the engineering stress-strain curve. This corresponds to the maximum stress that can be sustained by a structure in tension. Ultimate tensile strength is often shortened to “tensile strength” or even to “the ultimate.” If this stress is applied and maintained, fracture will result. Often, this value is significantly more than the yield stress (as much as 50 to 60 percent more than the yield for some types of metals). When a ductile material reaches its ultimate strength, it experiences necking where the cross-sectional area reduces locally. The stress-strain curve contains no higher stress than the ultimate strength. Even though deformations can continue to increase, the stress usually decreases after the ultimate strength has been achieved. It is an intensive property; therefore its value does not depend on the size of the test specimen. However, it is dependent on other factors, such as the preparation of the specimen, the presence or otherwise of surface defects, and the temperature of the test environment and material. Ultimate tensile strengths vary from 50 MPa for an aluminum to as high as 3000 MPa for very high-strength steels.

The ultimate tensile strength is the maximum on the engineering stress-strain curve. This corresponds to the maximum stress that can be sustained by a structure in tension. Ultimate tensile strength is often shortened to “tensile strength” or even to “the ultimate.” If this stress is applied and maintained, fracture will result. Often, this value is significantly more than the yield stress (as much as 50 to 60 percent more than the yield for some types of metals). When a ductile material reaches its ultimate strength, it experiences necking where the cross-sectional area reduces locally. The stress-strain curve contains no higher stress than the ultimate strength. Even though deformations can continue to increase, the stress usually decreases after the ultimate strength has been achieved. It is an intensive property; therefore its value does not depend on the size of the test specimen. However, it is dependent on other factors, such as the preparation of the specimen, the presence or otherwise of surface defects, and the temperature of the test environment and material. Ultimate tensile strengths vary from 50 MPa for an aluminum to as high as 3000 MPa for very high-strength steels.

Yield Strength

Yield strength of aluminium bronze – UNS C95400 is about 250 MPa.

Yield strength of tin bronze – UNS C90500 – gun metal is about 150 MPa.

Yield strength of copper beryllium – UNS C17200 is about 1100 MPa.

The yield point is the point on a stress-strain curve that indicates the limit of elastic behavior and the beginning plastic behavior. Yield strength or yield stress is the material property defined as the stress at which a material begins to deform plastically whereas yield point is the point where nonlinear (elastic + plastic) deformation begins. Prior to the yield point, the material will deform elastically and will return to its original shape when the applied stress is removed. Once the yield point is passed, some fraction of the deformation will be permanent and non-reversible. Some steels and other materials exhibit a behaviour termed a yield point phenomenon. Yield strengths vary from 35 MPa for a low-strength aluminum to greater than 1400 MPa for very high-strength steels.

Young’s Modulus of Elasticity

Young’s modulus of elasticity of aluminium bronze – UNS C95400 is about 110 GPa.

Young’s modulus of elasticity of tin bronze – UNS C90500 – gun metal is about 103 GPa.

Young’s modulus of elasticity of copper beryllium – UNS C17200 is about 131 GPa.

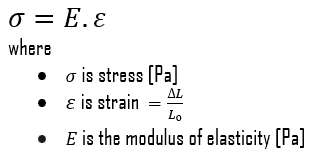

The Young’s modulus of elasticity is the elastic modulus for tensile and compressive stress in the linear elasticity regime of a uniaxial deformation and is usually assessed by tensile tests. Up to a limiting stress, a body will be able to recover its dimensions on removal of the load. The applied stresses cause the atoms in a crystal to move from their equilibrium position. All the atoms are displaced the same amount and still maintain their relative geometry. When the stresses are removed, all the atoms return to their original positions and no permanent deformation occurs. According to the Hooke’s law, the stress is proportional to the strain (in the elastic region), and the slope is Young’s modulus. Young’s modulus is equal to the longitudinal stress divided by the strain.

We hope, this article, Strength of Bronzes, helps you. If so, give us a like in the sidebar. Main purpose of this website is to help the public to learn some interesting and important information about materials and their properties.