Magnesium alloys are mixtures of magnesium and other alloying metal, usually aluminium, zinc, silicon, manganese, copper and zirconium. Since the most outstanding characteristic of magnesium is its density, 1.7 g/cm3, its alloys are used where light weight is an important consideration (e.g., in aircraft components). Magnesium has the lowest melting point (923 K (1,202 °F)) of all the alkaline earth metals. Pure magnesium has an HCP crystal structure, is relatively soft, and has a low elastic modulus: 45 GPa. Magnesium alloys have also a hexagonal lattice structure, which affects the fundamental properties of these alloys. At room temperature, magnesium and its alloys are difficult to perform cold working due to the fact plastic deformation of the hexagonal lattice is more complicated than in cubic latticed metals like aluminium, copper and steel. Therefore, magnesium alloys are typically used as cast alloys. Despite the reactive nature of the pure magnesium powder, magnesium metal and its alloys have good resistance to corrosion.

Magnesium alloys are mixtures of magnesium and other alloying metal, usually aluminium, zinc, silicon, manganese, copper and zirconium. Since the most outstanding characteristic of magnesium is its density, 1.7 g/cm3, its alloys are used where light weight is an important consideration (e.g., in aircraft components). Magnesium has the lowest melting point (923 K (1,202 °F)) of all the alkaline earth metals. Pure magnesium has an HCP crystal structure, is relatively soft, and has a low elastic modulus: 45 GPa. Magnesium alloys have also a hexagonal lattice structure, which affects the fundamental properties of these alloys. At room temperature, magnesium and its alloys are difficult to perform cold working due to the fact plastic deformation of the hexagonal lattice is more complicated than in cubic latticed metals like aluminium, copper and steel. Therefore, magnesium alloys are typically used as cast alloys. Despite the reactive nature of the pure magnesium powder, magnesium metal and its alloys have good resistance to corrosion.

Aluminium is the most common alloying element. Aluminium, zinc, zirconium, and thorium promote precipitation hardening: manganese improves corrosion resistance; and tin improves castability.

We must add, pure magnesium is highly flammable, especially when powdered or shaved into thin strips, though it is difficult to ignite in mass or bulk. It produces intense, bright, white light when it burns. Flame temperatures of magnesium and some magnesium alloys can reach 3,100°C. Burning or molten magnesium reacts violently with water. Once ignited, such fires are difficult to extinguish, because combustion continues in nitrogen (forming magnesium nitride), carbon dioxide (forming magnesium oxide and carbon), and water. Burning magnesium can be quenched by using a Class D dry chemical fire extinguisher. Its flammability is greatly reduced by a small amount of calcium in the alloy.

Properties of Magnesium Alloys

Material properties are intensive properties, that means they are independent of the amount of mass and may vary from place to place within the system at any moment. The basis of materials science involves studying the structure of materials, and relating them to their properties (mechanical, electrical etc.). Once a materials scientist knows about this structure-property correlation, they can then go on to study the relative performance of a material in a given application. The major determinants of the structure of a material and thus of its properties are its constituent chemical elements and the way in which it has been processed into its final form.

Mechanical Properties of Magnesium Alloys

Materials are frequently chosen for various applications because they have desirable combinations of mechanical characteristics. For structural applications, material properties are crucial and engineers must take them into account.

Strength of Magnesium Alloys

In mechanics of materials, the strength of a material is its ability to withstand an applied load without failure or plastic deformation. Strength of materials basically considers the relationship between the external loads applied to a material and the resulting deformation or change in material dimensions. Strength of a material is its ability to withstand this applied load without failure or plastic deformation.

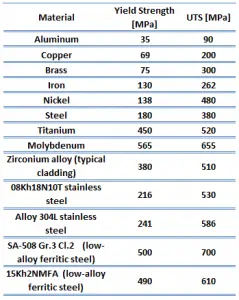

Ultimate Tensile Strength

Ultimate tensile strength of Elektron 21 – UNS M12310 is about 280 MPa.

The ultimate tensile strength is the maximum on the engineering stress-strain curve. This corresponds to the maximum stress that can be sustained by a structure in tension. Ultimate tensile strength is often shortened to “tensile strength” or even to “the ultimate.” If this stress is applied and maintained, fracture will result. Often, this value is significantly more than the yield stress (as much as 50 to 60 percent more than the yield for some types of metals). When a ductile material reaches its ultimate strength, it experiences necking where the cross-sectional area reduces locally. The stress-strain curve contains no higher stress than the ultimate strength. Even though deformations can continue to increase, the stress usually decreases after the ultimate strength has been achieved. It is an intensive property; therefore its value does not depend on the size of the test specimen. However, it is dependent on other factors, such as the preparation of the specimen, the presence or otherwise of surface defects, and the temperature of the test environment and material. Ultimate tensile strengths vary from 50 MPa for an aluminum to as high as 3000 MPa for very high-strength steels.

The ultimate tensile strength is the maximum on the engineering stress-strain curve. This corresponds to the maximum stress that can be sustained by a structure in tension. Ultimate tensile strength is often shortened to “tensile strength” or even to “the ultimate.” If this stress is applied and maintained, fracture will result. Often, this value is significantly more than the yield stress (as much as 50 to 60 percent more than the yield for some types of metals). When a ductile material reaches its ultimate strength, it experiences necking where the cross-sectional area reduces locally. The stress-strain curve contains no higher stress than the ultimate strength. Even though deformations can continue to increase, the stress usually decreases after the ultimate strength has been achieved. It is an intensive property; therefore its value does not depend on the size of the test specimen. However, it is dependent on other factors, such as the preparation of the specimen, the presence or otherwise of surface defects, and the temperature of the test environment and material. Ultimate tensile strengths vary from 50 MPa for an aluminum to as high as 3000 MPa for very high-strength steels.

Yield Strength

Yield strength of Elektron 21 – UNS M12310 is about 145 MPa.

The yield point is the point on a stress-strain curve that indicates the limit of elastic behavior and the beginning plastic behavior. Yield strength or yield stress is the material property defined as the stress at which a material begins to deform plastically whereas yield point is the point where nonlinear (elastic + plastic) deformation begins. Prior to the yield point, the material will deform elastically and will return to its original shape when the applied stress is removed. Once the yield point is passed, some fraction of the deformation will be permanent and non-reversible. Some steels and other materials exhibit a behaviour termed a yield point phenomenon. Yield strengths vary from 35 MPa for a low-strength aluminum to greater than 1400 MPa for very high-strength steels.

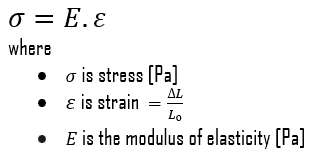

Young’s Modulus of Elasticity

Young’s modulus of elasticity of Elektron 21 – UNS M12310 is about 45 GPa.

The Young’s modulus of elasticity is the elastic modulus for tensile and compressive stress in the linear elasticity regime of a uniaxial deformation and is usually assessed by tensile tests. Up to a limiting stress, a body will be able to recover its dimensions on removal of the load. The applied stresses cause the atoms in a crystal to move from their equilibrium position. All the atoms are displaced the same amount and still maintain their relative geometry. When the stresses are removed, all the atoms return to their original positions and no permanent deformation occurs. According to the Hooke’s law, the stress is proportional to the strain (in the elastic region), and the slope is Young’s modulus. Young’s modulus is equal to the longitudinal stress divided by the strain.

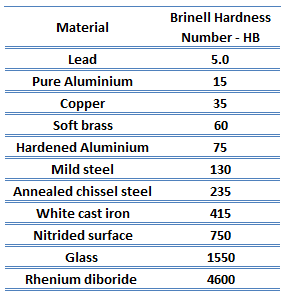

Hardness of Magnesium Alloys

Brinell hardness of Elektron 21 – UNS M12310 is approximately 70 HB.

Rockwell hardness test is one of the most common indentation hardness tests, that has been developed for hardness testing. In contrast to Brinell test, the Rockwell tester measures the depth of penetration of an indenter under a large load (major load) compared to the penetration made by a preload (minor load). The minor load establishes the zero position. The major load is applied, then removed while still maintaining the minor load. The difference between depth of penetration before and after application of the major load is used to calculate the Rockwell hardness number. That is, the penetration depth and hardness are inversely proportional. The chief advantage of Rockwell hardness is its ability to display hardness values directly. The result is a dimensionless number noted as HRA, HRB, HRC, etc., where the last letter is the respective Rockwell scale.

The Rockwell C test is performed with a Brale penetrator (120°diamond cone) and a major load of 150kg.

Thermal Properties of Magnesium Alloys

Thermal properties of materials refer to the response of materials to changes in their thermodynamics/thermodynamic-properties/what-is-temperature-physics/”>temperature and to the application of heat. As a solid absorbs thermodynamics/what-is-energy-physics/”>energy in the form of heat, its temperature rises and its dimensions increase. But different materials react to the application of heat differently.

Heat capacity, thermal expansion, and thermal conductivity are properties that are often critical in the practical use of solids.

Melting Point of Magnesium Alloys

Melting point of Elektron 21 – UNS M12310 is around 550 – 640°C.

In general, melting is a phase change of a substance from the solid to the liquid phase. The melting point of a substance is the temperature at which this phase change occurs. The melting point also defines a condition in which the solid and liquid can exist in equilibrium.

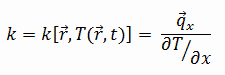

Thermal Conductivity of Magnesium Alloys

The thermal conductivity of Elektron 21 – UNS M12310 is 116 W/(m.K).

The heat transfer characteristics of a solid material are measured by a property called the thermal conductivity, k (or λ), measured in W/m.K. It is a measure of a substance’s ability to transfer heat through a material by conduction. Note that Fourier’s law applies for all matter, regardless of its state (solid, liquid, or gas), therefore, it is also defined for liquids and gases.

The thermal conductivity of most liquids and solids varies with temperature. For vapors, it also depends upon pressure. In general:

Most materials are very nearly homogeneous, therefore we can usually write k = k (T). Similar definitions are associated with thermal conductivities in the y- and z-directions (ky, kz), but for an isotropic material the thermal conductivity is independent of the direction of transfer, kx = ky = kz = k.

We hope, this article, Properties of Magnesium Alloys, helps you. If so, give us a like in the sidebar. Main purpose of this website is to help the public to learn some interesting and important information about materials and their properties.