Geiger-Marsden Experiments – Rutherford gold foil experiment

The Rutherford model of the atom is a model of the atom devised by the British physicist Ernest Rutherford. Rutherford’s new model for the atom is based on the experimental results, which were obtained from Geiger-Marsden experiments (also called the Rutherford gold foil experiment). The Geiger–Marsden experiments were performed between 1908 and 1913 by Hans Geiger (of Geiger counter fame) and Ernest Marsden (a 20-year-old student who had not yet earned his bachelor’s degree) under the direction of Ernest Rutherford.

The Rutherford model of the atom is a model of the atom devised by the British physicist Ernest Rutherford. Rutherford’s new model for the atom is based on the experimental results, which were obtained from Geiger-Marsden experiments (also called the Rutherford gold foil experiment). The Geiger–Marsden experiments were performed between 1908 and 1913 by Hans Geiger (of Geiger counter fame) and Ernest Marsden (a 20-year-old student who had not yet earned his bachelor’s degree) under the direction of Ernest Rutherford.

Rutherford’s idea was to direct energetic alpha particles at a thin metal foil and measure how an alpha particle beam is scattered when it strikes a thin metal foil. A narrow collimated beam of alpha particles was aimed at a gold foil of approximately 1 μm thickness (about 10,000 atoms thick). Alpha particles are energetic nuclei of helium (usually about 6 MeV). Alpha particles, which are about 7300 times more massive than electrons, have a positive charge of +2e. Because of their relatively much greater mass, alpha particles are not significantly deflected from their paths by the electrons in the metal’s atoms.

According to Thomson’s model, if an alpha particle were to collide with an plum-pudding atom, it would just fly straight through, its path being deflected by at most a fraction of a degree. But in the experiment Geiger and Marsden saw that most of the particles are scattered through rather small angles, but, and this was the big surprise, a very small fraction of them are scattered through very large angles, approaching 180° (i.e., they were recoiled backwards).

In Rutherford’s words:

“It is almost as incredible as if you had fired a fifteen inch shell at a sheet of tissue paper and it came back and hit you.”

Rutherford assumed that, to deflect the alpha particle backward, there must be a very large force. This force could be provided only result from a collision with a massive target or from an interaction with an electric or magnetic field of great strength. In previous experiments, it was shown the deflections had to be electrical or perhaps possibly magnetic in origin.

Rutherford assumed that, to deflect the alpha particle backward, there must be a very large force. This force could be provided only result from a collision with a massive target or from an interaction with an electric or magnetic field of great strength. In previous experiments, it was shown the deflections had to be electrical or perhaps possibly magnetic in origin.

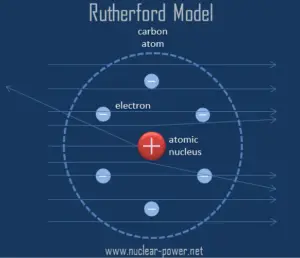

As a result, Rutherford abandoned the Thomson model. Geiger-Marsden experiments were therefore a landmark series of experiments by which scientists discovered that every atom contains a nucleus (whose diameter is of the order 10-14m.) where all of its positive charge and most of its mass are concentrated in a small region called an atomic nucleus. In Rutherford’s atom, the diameter of its sphere (about 10-10 m) of influence is determined by its electrons. In other words, the nucleus occupies only about 10-12 of the total volume of the atom or less (the nuclear atom is largely empty space), but it contains all the positive charge and at least 99.95% of the total mass of the atom.

Based on these results, Ernest Rutherford proposed a new model of the atom. He postulated that the positive charge in an atom is concentrated in a small region (in comparison to the rest of the atom) called a nucleus at the center of the atom with electrons existing in orbits around it. Furthermore, the nucleus is responsible for most of the mass of the atom.

We hope, this article, Geiger-Marsden Experiment – Rutherford gold foil experiment, helps you. If so, give us a like in the sidebar. Main purpose of this website is to help the public to learn some interesting and important information about materials and their properties.