Steels are iron–carbon alloys that may contain appreciable concentrations of other alloying elements. Adding a small amount of non-metallic carbon to iron trades its great ductility for the greater strength. Due to its very-high strength, but still substantial toughness, and its ability to be greatly altered by heat treatment, steel is one of the most useful and common ferrous alloy in modern use. There are thousands of alloys that have different compositions and/or heat treatments. The mechanical properties are sensitive to the content of carbon, which is normally less than 1.0 wt%. According ot AISI classification, carbon steel is broken down into four classes based on carbon content.

Steels consist of iron (Fe) alloyed with carbon (C) (about 0.1% to 1%, depending on type). Adding a small amount of non-metallic carbon to iron trades its great ductility for the greater strength. Due to its very-high strength, but still substantial toughness, and its ability to be greatly altered by heat treatment, steel is one of the most useful and common ferrous alloy in modern use. Their widespread use is accounted for by following factors:

- Iron containing compounds exist in abundant quantities within the Earth’s crust.

- Metallic iron and steel alloys may be produced using relatively economical extraction, refining, alloying, and fabrication techniques

- Ferrous alloys are extremely versatile, in that they may be tailored to have a wide range of mechanical and physical properties.

The principal disadvantage of many ferrous alloys is their susceptibility to corrosion. By adding chromium to steel, its resistance to corrosion can be enhanced, creating stainless steel, while adding silicon will alter its electrical characteristics, producing silicon steel.

Hardness of Steels

In materials science, hardness is the ability to withstand surface indentation (localized plastic deformation) and scratching. Hardness is probably the most poorly defined material property because it may indicate resistance to scratching, resistance to abrasion, resistance to indentation or even resistance to shaping or localized plastic deformation. Hardness is important from an engineering standpoint because resistance to wear by either friction or erosion by steam, oil, and water generally increases with hardness.

In materials science, hardness is the ability to withstand surface indentation (localized plastic deformation) and scratching. Hardness is probably the most poorly defined material property because it may indicate resistance to scratching, resistance to abrasion, resistance to indentation or even resistance to shaping or localized plastic deformation. Hardness is important from an engineering standpoint because resistance to wear by either friction or erosion by steam, oil, and water generally increases with hardness.

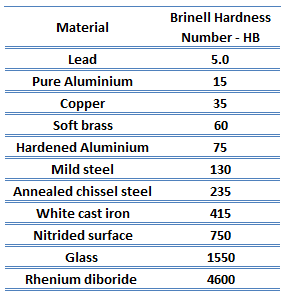

Brinell hardness test is one of indentation hardness tests, that has been developed for hardness testing. In Brinell tests, a hard, spherical indenter is forced under a specific load into the surface of the metal to be tested. The typical test uses a 10 mm (0.39 in) diameter hardened steel ball as an indenter with a 3,000 kgf (29.42 kN; 6,614 lbf) force. The load is maintained constant for a specified time (between 10 and 30 s). For softer materials, a smaller force is used; for harder materials, a tungsten carbide ball is substituted for the steel ball.

The test provides numerical results to quantify the hardness of a material, which is expressed by the Brinell hardness number – HB. The Brinell hardness number is designated by the most commonly used test standards (ASTM E10-14[2] and ISO 6506–1:2005) as HBW (H from hardness, B from brinell and W from the material of the indenter, tungsten (wolfram) carbide). In former standards HB or HBS were used to refer to measurements made with steel indenters.

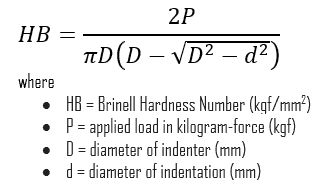

The Brinell hardness number (HB) is the load divided by the surface area of the indentation. The diameter of the impression is measured with a microscope with a superimposed scale. The Brinell hardness number is computed from the equation:

There are a variety of test methods in common use (e.g. Brinell, Knoop, Vickers and Rockwell). There are tables that are available correlating the hardness numbers from the different test methods where correlation is applicable. In all scales, a high hardness number represents a hard metal.

Example – Hardness of Low-carbon Steel

Brinell hardness of low-carbon steel is approximately 120 MPa.

Example – Hardness of High-carbon Steel

Brinell hardness of high-carbon steel is approximately 200 MPa.

Example – Hardness of Damascus Steel

Rockwell hardness of Damascus steel depends on the current type of the steel, but it may be approximately 62-64 HRC Rockwell.

We hope, this article, Hardness of Steels, helps you. If so, give us a like in the sidebar. Main purpose of this website is to help the public to learn some interesting and important information about materials and their properties.