Chemical Properties of Atoms

Every solid, liquid, gas, and plasma is composed of neutral or ionized atoms. The chemical properties of the atom are determined by the number of protons, in fact, by number and arrangement of electrons. The configuration of these electrons follows from the principles of quantum mechanics. The number of electrons in each element’s electron shells, particularly the outermost valence shell, is the primary factor in determining its chemical bonding behavior. In the periodic table, the elements are listed in order of increasing atomic number Z.

The total number of protons in the nucleus of an atom is called the atomic number (or the proton number) of the atom and is given the symbol Z. The number of electrons in an electrically-neutral atom is the same as the number of protons in the nucleus. The total electrical charge of the nucleus is therefore +Ze, where e (elementary charge) equals to 1,602 x 10-19coulombs. Each electron is influenced by the electric fields produced by the positive nuclear charge and the other (Z – 1) negative electrons in the atom.

It is the Pauli exclusion principle that requires the electrons in an atom to occupy different energy levels instead of them all condensing in the ground state. The ordering of the electrons in the ground state of multielectron atoms, starts with the lowest energy state (ground state) and moves progressively from there up the energy scale until each of the atom’s electrons has been assigned a unique set of quantum numbers. This fact has key implications for the building up of the periodic table of elements.

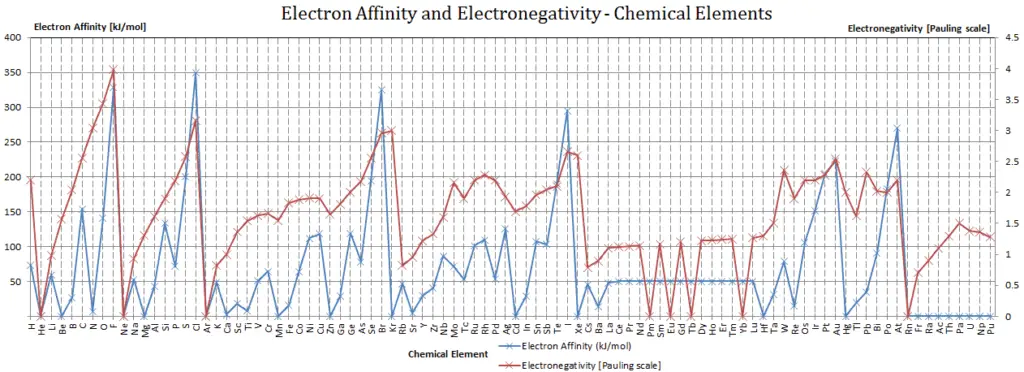

Electron Affinity

In chemistry and atomic physics, the electron affinity of an atom or molecule is defined as:

the change in energy (in kJ/mole) of a neutral atom or molecule (in the gaseous phase) when an electron is added to the atom to form a negative ion.

X + e– → X– + energy Affinity = – ∆H

In other words, it can be expressed as the neutral atom’s likelihood of gaining an electron. Note that, ionization energies measure the tendency of a neutral atom to resist the loss of electrons. Electron affinities are more difficult to measure than ionization energies.

A fluorine atom in the gas phase, for example, gives off energy when it gains an electron to form a fluoride ion.

F + e– → F– – ∆H = Affinity = 328 kJ/mol

To use electron affinities properly, it is essential to keep track of sign. When an electron is added to a neutral atom, energy is released. This affinity is known as the first electron affinity and these energies are negative. By convention, the negative sign shows a release of energy. However, more energy is required to add an electron to a negative ion which overwhelms any the release of energy from the electron attachment process. This affinity is known as the second electron affinity and these energies are positive.

Affinities of Non metals vs. Affinities of Metals

- Metals: Metals like to lose valence electrons to form cations to have a fully stable shell. The electron affinity of metals is lower than that of nonmetals. Mercury most weakly attracts an extra electron.

- Nonmetals: Generally, nonmetals have more positive electron affinity than metals. Nonmetals like to gain electrons to form anions to have a fully stable electron shell. Chlorine most strongly attracts extra electrons. The electron affinities of the noble gases have not been conclusively measured, so they may or may not have slightly negative values.

Electronegativity

Electronegativity, symbol χ, is a chemical property that describes the tendency of an atom to attract electrons towards this atom. For this purposes, a dimensionless quantity the Pauling scale, symbol χ, is the most commonly used.

The electronegativity of fluorine is:

χ = 4.0

In general, an atom’s electronegativity is affected by both its atomic number and the distance at which its valence electrons reside from the charged nucleus. The higher the associated electronegativity number, the more an element or compound attracts electrons towards it.

The most electronegative atom, fluorine, is assigned a value of 4.0, and values range down to cesium and francium which are the least electronegative at 0.7.

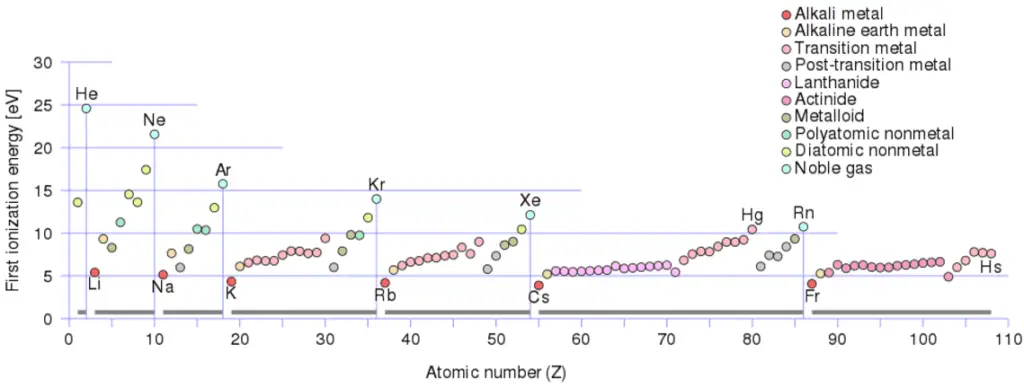

Ionization Energy

Ionization energy, also called ionization potential, is the energy necessary to remove an electron from the neutral atom.

X + energy → X+ + e−

where X is any atom or molecule capable of being ionized, X+ is that atom or molecule with an electron removed (positive ion), and e− is the removed electron.

A nitrogen atom, for example, requires the following ionization energy to remove the outermost electron.

N + IE → N+ + e− IE = 14.5 eV

The ionization energy associated with removal of the first electron is most commonly used. The nth ionization energy refers to the amount of energy required to remove an electron from the species with a charge of (n-1).

1st ionization energy

X → X+ + e−

2nd ionization energy

X+ → X2+ + e−

3rd ionization energy

X2+ → X3+ + e−

Ionization Energy for different Elements

There is an ionization energy for each successive electron removed. The electrons that circle the nucleus move in fairly well-defined orbits. Some of these electrons are more tightly bound in the atom than others. For example, only 7.38 eV is required to remove the outermost electron from a lead atom, while 88,000 eV is required to remove the innermost electron. Helps to understand reactivity of elements (especially metals, which lose electrons).

In general, the ionization energy increases moving up a group and moving left to right across a period. Moreover:

- Ionization energy is lowest for the alkali metals which have a single electron outside a closed shell.

- Ionization energy increases across a row on the periodic maximum for the noble gases which have closed shells

For example, sodium requires only 496 kJ/mol or 5.14 eV/atom to ionize it. On the other hand neon, the noble gas, immediately preceding it in the periodic table, requires 2081 kJ/mol or 21.56 eV/atom.

We hope, this article, Chemical Property of Atoms, helps you. If so, give us a like in the sidebar. Main purpose of this website is to help the public to learn some interesting and important information about materials and their properties.