In metallurgy, stainless steel is a steel alloy with at least 10.5% chromium with or without other alloying elements and a maximum of 1.2% carbon by mass. Stainless steels, also known as inox steels or inox from French inoxydable (inoxidizable), are steel alloys, which are very well known for their corrosion resistance, which increases with increasing chromium content. Corrosion resistance may also be enhanced by nickel and molybdenum additions. The resistance of these metallic alloys to the chemical effects of corrosive agents is based on passivation. For passivation to occur and remain stable, the Fe-Cr alloy must have a minimum chromium content of about 10.5% by weight, above which passivity can occur and below which it is impossible. Chromium can be used as a hardening element and is frequently used with a toughening element such as nickel to produce superior mechanical properties.

In metallurgy, stainless steel is a steel alloy with at least 10.5% chromium with or without other alloying elements and a maximum of 1.2% carbon by mass. Stainless steels, also known as inox steels or inox from French inoxydable (inoxidizable), are steel alloys, which are very well known for their corrosion resistance, which increases with increasing chromium content. Corrosion resistance may also be enhanced by nickel and molybdenum additions. The resistance of these metallic alloys to the chemical effects of corrosive agents is based on passivation. For passivation to occur and remain stable, the Fe-Cr alloy must have a minimum chromium content of about 10.5% by weight, above which passivity can occur and below which it is impossible. Chromium can be used as a hardening element and is frequently used with a toughening element such as nickel to produce superior mechanical properties.

Austenitic Stainless Steel

Austenitic stainless steels contain between 16 and 25% of chromium and can also contain nitrogen in solution, both of which contribute to their relatively high corrosion resistance. Austenitic stainless steels are classified with AISI 200- or 300-series designations; the 300-series grades are chromium-nickel alloys, and the 200-series represent a set of compositions in which manganese and/or nitrogen replace some of the nickel. Austenitic stainless steels have the best corrosion resistance of all stainless steels and they have excellent cryogenic properties, and good high-temperature strength. They possess a face-centered cubic (fcc) microstructure that is nonmagnetic, and they can be easily welded. This austenite crystalline structure is achieved by sufficient additions of the austenite stabilizing elements nickel, manganese and nitrogen. Austenitic stainless steel is the largest family of stainless steels, making up about two-thirds of all stainless steel production. Their yield strength is low (200 to 300MPa), which limits their use for structural and other load bearing components. They cannot be hardened by heat treatment but have the useful property of being able to be work hardened to high strength levels whilst retaining a useful level of ductility and toughness. Duplex stainless steels tend to be preferred in such situations because of their high strength and corrosion resistance. The best known grade is AISI 304 stainless, which contains both chromium (between 15% and 20%) and nickel (between 2% and 10.5%) metals as the main non-iron constituents. 304 stainless steel has excellent resistance to a wide range of atmospheric environments and many corrosive media. These alloys are usually characterized as ductile, weldable, and hardenable by cold forming.

Austenitic stainless steels contain between 16 and 25% of chromium and can also contain nitrogen in solution, both of which contribute to their relatively high corrosion resistance. Austenitic stainless steels are classified with AISI 200- or 300-series designations; the 300-series grades are chromium-nickel alloys, and the 200-series represent a set of compositions in which manganese and/or nitrogen replace some of the nickel. Austenitic stainless steels have the best corrosion resistance of all stainless steels and they have excellent cryogenic properties, and good high-temperature strength. They possess a face-centered cubic (fcc) microstructure that is nonmagnetic, and they can be easily welded. This austenite crystalline structure is achieved by sufficient additions of the austenite stabilizing elements nickel, manganese and nitrogen. Austenitic stainless steel is the largest family of stainless steels, making up about two-thirds of all stainless steel production. Their yield strength is low (200 to 300MPa), which limits their use for structural and other load bearing components. They cannot be hardened by heat treatment but have the useful property of being able to be work hardened to high strength levels whilst retaining a useful level of ductility and toughness. Duplex stainless steels tend to be preferred in such situations because of their high strength and corrosion resistance. The best known grade is AISI 304 stainless, which contains both chromium (between 15% and 20%) and nickel (between 2% and 10.5%) metals as the main non-iron constituents. 304 stainless steel has excellent resistance to a wide range of atmospheric environments and many corrosive media. These alloys are usually characterized as ductile, weldable, and hardenable by cold forming.

Stainless Steel – Type 304

Type 304 stainless steel (containing 18%-20% chromium and 8%-10.5% nickel) is the most common stainless steel. It is also known as “18/8” stainless steel because of its composition, which includes 18% chromium and 8% nickel. This alloy resists most types of corrosion. It is an austenitic stainless steel and it has also excellent cryogenic properties, and good high-temperature strength as well as good forming and welding properties. It is less electrically and thermally conductive than carbon steel and is essentially non-magnetic.

Type 304L stainless steel, which is widely used in nuclear industry, is an extra-low carbon version of the 304 steel alloy. This grade has slightly lower mechanical properties than the standard 304 grade, but is still widely used thanks to its versatility. The lower carbon content in 304L minimizes deleterious or harmful carbide precipitation as a result of welding. 304L can, therefore, be used “as welded” in severe corrosion environments, and it eliminates the need for annealing. Grade 304 has also good oxidation resistance in intermittent service to 870 °C, and in continuous service to 925 °C.

The body of the reactor vessel is constructed of a high-quality low-alloy carbon steel, and all surfaces that come into contact with reactor coolant are clad with a minimum of about 3 to 10 mm of austenitic stainless steel in order to minimize corrosion. Since grade 304L does not require post-weld annealing, it is extensively used in heavy gauge components.

Summary

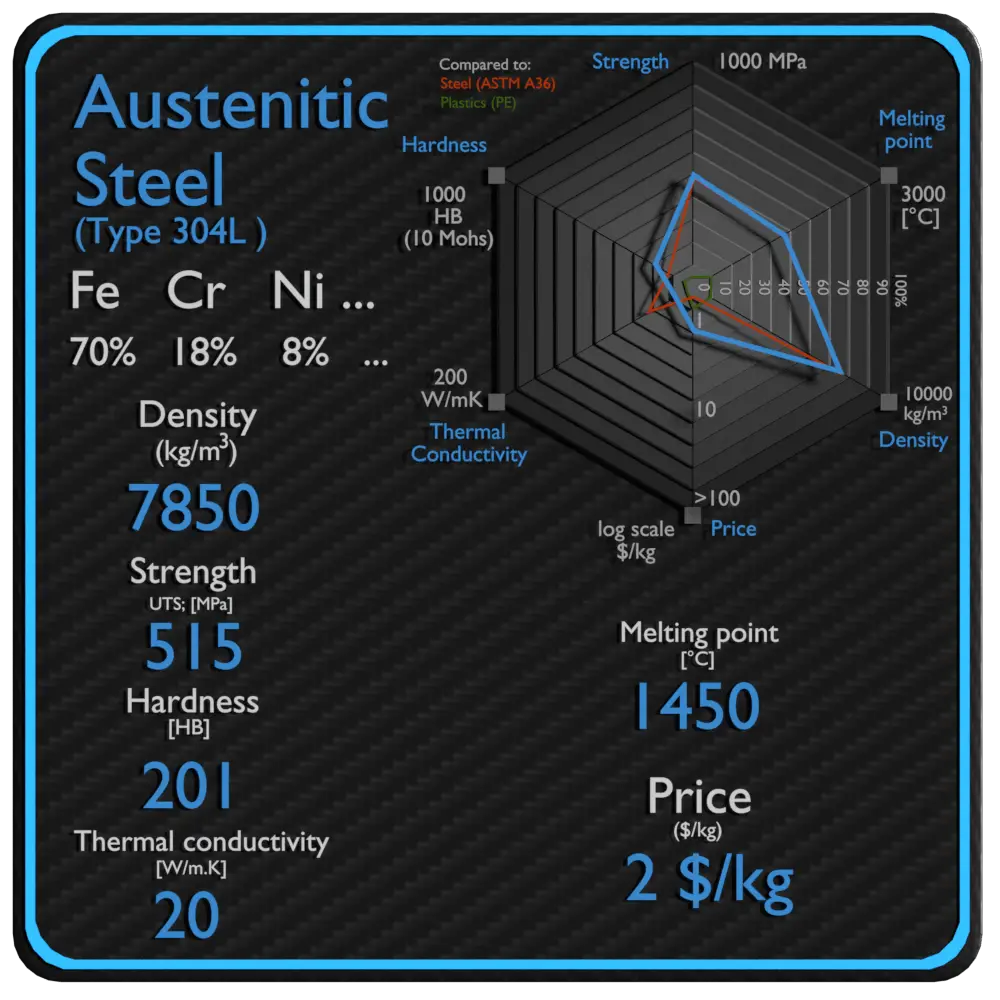

| Name | Austenitic Stainless Steel |

| Phase at STP | N/A |

| Density | 7850 kg/m3 |

| Ultimate Tensile Strength | 515 MPa |

| Yield Strength | 205 MPa |

| Young’s Modulus of Elasticity | 193 GPa |

| Brinell Hardness | 201 BHN |

| Melting Point | 1450 °C |

| Thermal Conductivity | 20 W/mK |

| Heat Capacity | 500 J/g K |

| Price | 2 $/kg |

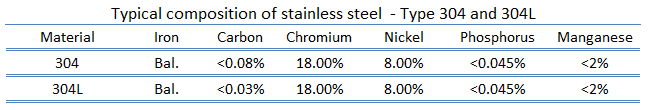

Composition of Austenitic Stainless Steel

Applications of Austenitic Stainless Steel

Application include motorsports and aerospace, since it possess high strength, light weight and it has excellent vibration damping characteristics. Magnesium alloys are used in a wide variety of structural and nonstructural applications. Structural applications include automotive, industrial, materials-handling, commercial, and aerospace equipment. Magnesium alloys are used for parts that operate at high speeds and thus must be light weight to minimize inertial forces. Commercial applications include hand-held tools, laptops, luggage, and ladders, automobiles (e.g., steering wheels and columns, seat frames, transmission cases).

Mechanical Properties of Austenitic Stainless Steel

Strength of Austenitic Stainless Steel

In mechanics of materials, the strength of a material is its ability to withstand an applied load without failure or plastic deformation. Strength of materials basically considers the relationship between the external loads applied to a material and the resulting deformation or change in material dimensions. In designing structures and machines, it is important to consider these factors, in order that the material selected will have adequate strength to resist applied loads or forces and retain its original shape.

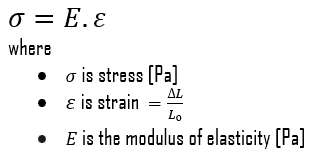

Strength of a material is its ability to withstand this applied load without failure or plastic deformation. For tensile stress, the capacity of a material or structure to withstand loads tending to elongate is known as ultimate tensile strength (UTS). Yield strength or yield stress is the material property defined as the stress at which a material begins to deform plastically whereas yield point is the point where nonlinear (elastic + plastic) deformation begins. In case of tensional stress of a uniform bar (stress-strain curve), the Hooke’s law describes behaviour of a bar in the elastic region. The Young’s modulus of elasticity is the elastic modulus for tensile and compressive stress in the linear elasticity regime of a uniaxial deformation and is usually assessed by tensile tests.

See also: Strength of Materials

Ultimate Tensile Strength of Austenitic Stainless Steel

Ultimate tensile strength of Austenitic Stainless Steel is 280 MPa.

Yield Strength of Austenitic Stainless Steel

Yield strength of Austenitic Stainless Steel is 145 MPa.

Modulus of Elasticity of Austenitic Stainless Steel

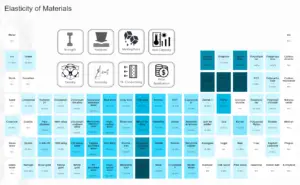

The Young’s modulus of elasticity of Austenitic Stainless Steel is 45 GPa.

Hardness of Austenitic Stainless Steel

In materials science, hardness is the ability to withstand surface indentation (localized plastic deformation) and scratching. Brinell hardness test is one of indentation hardness tests, that has been developed for hardness testing. In Brinell tests, a hard, spherical indenter is forced under a specific load into the surface of the metal to be tested.

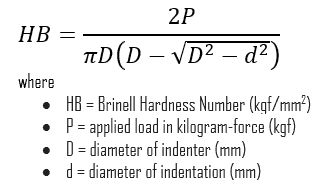

The Brinell hardness number (HB) is the load divided by the surface area of the indentation. The diameter of the impression is measured with a microscope with a superimposed scale. The Brinell hardness number is computed from the equation:

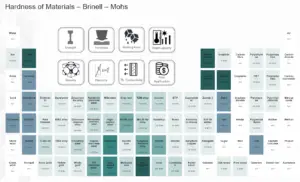

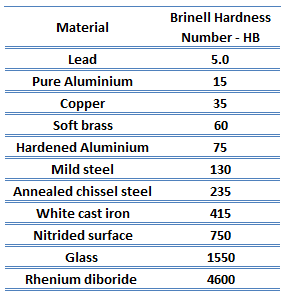

Brinell hardness of Austenitic Stainless Steel is approximately 70 BHN(converted).

See also: Hardness of Materials

Strength of Materials

Thermal Properties of Austenitic Stainless Steel

Austenitic Stainless Steel – Melting Point

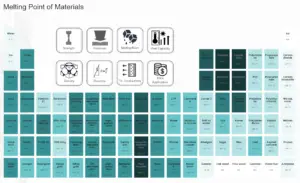

Melting point of Austenitic Stainless Steel is 550-640 °C.

Note that, these points are associated with the standard atmospheric pressure. In general, melting is a phase change of a substance from the solid to the liquid phase. The melting point of a substance is the temperature at which this phase change occurs. The melting point also defines a condition in which the solid and liquid can exist in equilibrium. For various chemical compounds and alloys, it is difficult to define the melting point, since they are usually a mixture of various chemical elements.

Austenitic Stainless Steel – Thermal Conductivity

Thermal conductivity of Austenitic Stainless Steel is 116 W/(m·K).

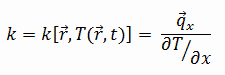

The heat transfer characteristics of a solid material are measured by a property called the thermal conductivity, k (or λ), measured in W/m.K. It is a measure of a substance’s ability to transfer heat through a material by conduction. Note that Fourier’s law applies for all matter, regardless of its state (solid, liquid, or gas), therefore, it is also defined for liquids and gases.

The thermal conductivity of most liquids and solids varies with temperature. For vapors, it also depends upon pressure. In general:

Most materials are very nearly homogeneous, therefore we can usually write k = k (T). Similar definitions are associated with thermal conductivities in the y- and z-directions (ky, kz), but for an isotropic material the thermal conductivity is independent of the direction of transfer, kx = ky = kz = k.

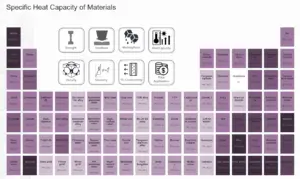

Austenitic Stainless Steel – Specific Heat

Specific heat of Austenitic Stainless Steel is 900 J/g K.

Specific heat, or specific heat capacity, is a property related to internal energy that is very important in thermodynamics. The intensive properties cv and cp are defined for pure, simple compressible substances as partial derivatives of the internal energy u(T, v) and enthalpy h(T, p), respectively:

where the subscripts v and p denote the variables held fixed during differentiation. The properties cv and cp are referred to as specific heats (or heat capacities) because under certain special conditions they relate the temperature change of a system to the amount of energy added by heat transfer. Their SI units are J/kg K or J/mol K.

Properties and prices of other materials

material-table-in-8k-resolution

[/lgc_column]Properties of Austenitic Stainless Steels

Material properties are intensive properties, that means they are independent of the amount of mass and may vary from place to place within the system at any moment. The basis of materials science involves studying the structure of materials, and relating them to their properties (mechanical, electrical etc.). Once a materials scientist knows about this structure-property correlation, they can then go on to study the relative performance of a material in a given application. The major determinants of the structure of a material and thus of its properties are its constituent chemical elements and the way in which it has been processed into its final form.

Mechanical Properties of Austenitic Stainless Steels

Materials are frequently chosen for various applications because they have desirable combinations of mechanical characteristics. For structural applications, material properties are crucial and engineers must take them into account.

Strength of Austenitic Stainless Steels

In mechanics of materials, the strength of a material is its ability to withstand an applied load without failure or plastic deformation. Strength of materials basically considers the relationship between the external loads applied to a material and the resulting deformation or change in material dimensions. Strength of a material is its ability to withstand this applied load without failure or plastic deformation.

Ultimate Tensile Strength

Ultimate tensile strength of stainless steel – type 304 is 515 MPa.

Ultimate tensile strength of stainless steel – type 304L is 485 MPa.

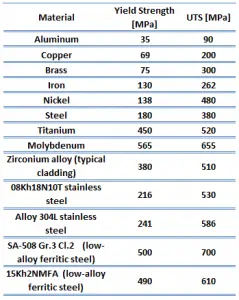

The ultimate tensile strength is the maximum on the engineering stress-strain curve. This corresponds to the maximum stress that can be sustained by a structure in tension. Ultimate tensile strength is often shortened to “tensile strength” or even to “the ultimate.” If this stress is applied and maintained, fracture will result. Often, this value is significantly more than the yield stress (as much as 50 to 60 percent more than the yield for some types of metals). When a ductile material reaches its ultimate strength, it experiences necking where the cross-sectional area reduces locally. The stress-strain curve contains no higher stress than the ultimate strength. Even though deformations can continue to increase, the stress usually decreases after the ultimate strength has been achieved. It is an intensive property; therefore its value does not depend on the size of the test specimen. However, it is dependent on other factors, such as the preparation of the specimen, the presence or otherwise of surface defects, and the temperature of the test environment and material. Ultimate tensile strengths vary from 50 MPa for an aluminum to as high as 3000 MPa for very high-strength steels.

The ultimate tensile strength is the maximum on the engineering stress-strain curve. This corresponds to the maximum stress that can be sustained by a structure in tension. Ultimate tensile strength is often shortened to “tensile strength” or even to “the ultimate.” If this stress is applied and maintained, fracture will result. Often, this value is significantly more than the yield stress (as much as 50 to 60 percent more than the yield for some types of metals). When a ductile material reaches its ultimate strength, it experiences necking where the cross-sectional area reduces locally. The stress-strain curve contains no higher stress than the ultimate strength. Even though deformations can continue to increase, the stress usually decreases after the ultimate strength has been achieved. It is an intensive property; therefore its value does not depend on the size of the test specimen. However, it is dependent on other factors, such as the preparation of the specimen, the presence or otherwise of surface defects, and the temperature of the test environment and material. Ultimate tensile strengths vary from 50 MPa for an aluminum to as high as 3000 MPa for very high-strength steels.

Yield Strength

Yield strength of stainless steel – type 304 is 205 MPa.

Yield strength of stainless steel – type 304L is 170 MPa.

The yield point is the point on a stress-strain curve that indicates the limit of elastic behavior and the beginning plastic behavior. Yield strength or yield stress is the material property defined as the stress at which a material begins to deform plastically whereas yield point is the point where nonlinear (elastic + plastic) deformation begins. Prior to the yield point, the material will deform elastically and will return to its original shape when the applied stress is removed. Once the yield point is passed, some fraction of the deformation will be permanent and non-reversible. Some steels and other materials exhibit a behaviour termed a yield point phenomenon. Yield strengths vary from 35 MPa for a low-strength aluminum to greater than 1400 MPa for very high-strength steels.

Young’s Modulus of Elasticity

Young’s modulus of elasticity stainless steel – type 304 and 304L is 193 GPa.

The Young’s modulus of elasticity is the elastic modulus for tensile and compressive stress in the linear elasticity regime of a uniaxial deformation and is usually assessed by tensile tests. Up to a limiting stress, a body will be able to recover its dimensions on removal of the load. The applied stresses cause the atoms in a crystal to move from their equilibrium position. All the atoms are displaced the same amount and still maintain their relative geometry. When the stresses are removed, all the atoms return to their original positions and no permanent deformation occurs. According to the Hooke’s law, the stress is proportional to the strain (in the elastic region), and the slope is Young’s modulus. Young’s modulus is equal to the longitudinal stress divided by the strain.

Hardness of Austenitic Stainless Steels

Brinell hardness of stainless steel – type 304 is approximately 201 MPa.

In materials science, hardness is the ability to withstand surface indentation (localized plastic deformation) and scratching. Hardness is probably the most poorly defined material property because it may indicate resistance to scratching, resistance to abrasion, resistance to indentation or even resistance to shaping or localized plastic deformation. Hardness is important from an engineering standpoint because resistance to wear by either friction or erosion by steam, oil, and water generally increases with hardness.

In materials science, hardness is the ability to withstand surface indentation (localized plastic deformation) and scratching. Hardness is probably the most poorly defined material property because it may indicate resistance to scratching, resistance to abrasion, resistance to indentation or even resistance to shaping or localized plastic deformation. Hardness is important from an engineering standpoint because resistance to wear by either friction or erosion by steam, oil, and water generally increases with hardness.

Brinell hardness test is one of indentation hardness tests, that has been developed for hardness testing. In Brinell tests, a hard, spherical indenter is forced under a specific load into the surface of the metal to be tested. The typical test uses a 10 mm (0.39 in) diameter hardened steel ball as an indenter with a 3,000 kgf (29.42 kN; 6,614 lbf) force. The load is maintained constant for a specified time (between 10 and 30 s). For softer materials, a smaller force is used; for harder materials, a tungsten carbide ball is substituted for the steel ball.

The test provides numerical results to quantify the hardness of a material, which is expressed by the Brinell hardness number – HB. The Brinell hardness number is designated by the most commonly used test standards (ASTM E10-14[2] and ISO 6506–1:2005) as HBW (H from hardness, B from brinell and W from the material of the indenter, tungsten (wolfram) carbide). In former standards HB or HBS were used to refer to measurements made with steel indenters.

The Brinell hardness number (HB) is the load divided by the surface area of the indentation. The diameter of the impression is measured with a microscope with a superimposed scale. The Brinell hardness number is computed from the equation:

There are a variety of test methods in common use (e.g. Brinell, Knoop, Vickers and Rockwell). There are tables that are available correlating the hardness numbers from the different test methods where correlation is applicable. In all scales, a high hardness number represents a hard metal.

Thermal Properties of Austenitic Stainless Steels

Thermal properties of materials refer to the response of materials to changes in their thermodynamics/thermodynamic-properties/what-is-temperature-physics/”>temperature and to the application of heat. As a solid absorbs thermodynamics/what-is-energy-physics/”>energy in the form of heat, its temperature rises and its dimensions increase. But different materials react to the application of heat differently.

Heat capacity, thermal expansion, and thermal conductivity are properties that are often critical in the practical use of solids.

Melting Point of Austenitic Stainless Steels

Melting point of stainless steel – type 304 steel is around 1450°C.

In general, melting is a phase change of a substance from the solid to the liquid phase. The melting point of a substance is the temperature at which this phase change occurs. The melting point also defines a condition in which the solid and liquid can exist in equilibrium.

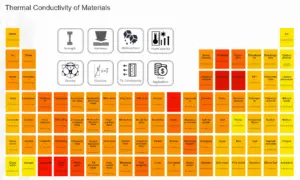

Thermal Conductivity of Austenitic Stainless Steels

The thermal conductivity of stainless steel – type 304 is 20 W/(m.K).

The heat transfer characteristics of a solid material are measured by a property called the thermal conductivity, k (or λ), measured in W/m.K. It is a measure of a substance’s ability to transfer heat through a material by conduction. Note that Fourier’s law applies for all matter, regardless of its state (solid, liquid, or gas), therefore, it is also defined for liquids and gases.

The thermal conductivity of most liquids and solids varies with temperature. For vapors, it also depends upon pressure. In general:

Most materials are very nearly homogeneous, therefore we can usually write k = k (T). Similar definitions are associated with thermal conductivities in the y- and z-directions (ky, kz), but for an isotropic material the thermal conductivity is independent of the direction of transfer, kx = ky = kz = k.

We hope, this article, Austenitic Stainless Steel, helps you. If so, give us a like in the sidebar. Main purpose of this website is to help the public to learn some interesting and important information about materials and their properties.