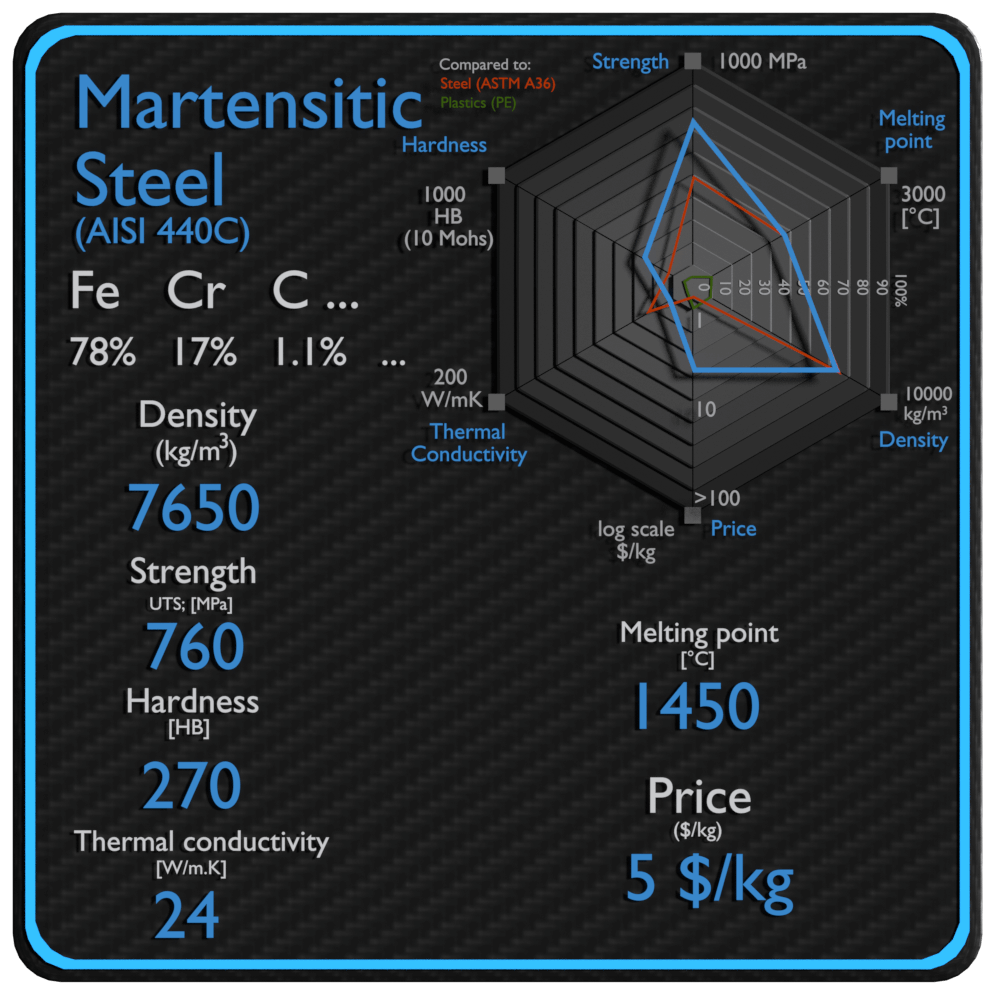

About Martensitic Stainless Steel

Martensitic stainless steels are similar to ferritic steels in being based on chromium but have higher carbon levels up as high as 1%. They are sometimes classified as low-carbon and high-carbon martensitic stainless steels. They contain 12 to 14% chromium, 0.2 to 1% molybdenum, and no significant amount of nickel. Higher amounts of carbon allows them to be hardened and tempered much like carbon and low-alloy steels. They have moderate corrosion resistance, but are considered hard, strong, slightly brittle. They are magnetic and they can be nondestructively tested using the magnetic particle inspection method, unlike austenitic stainless steel. A common martensitic stainless is AISI 440C, which contains 16 to 18% chromium and 0.95 to 1.2% carbon. Grade 440C stainless steel is used in the following applications: gage blocks, cutlery, ball bearings and races, molds and dies, knives.

Summary

| Name | Martensitic Stainless Steel |

| Phase at STP | solid |

| Density | 7650 kg/m3 |

| Ultimate Tensile Strength | 760 MPa |

| Yield Strength | 450 MPa |

| Young’s Modulus of Elasticity | 200 GPa |

| Brinell Hardness | 270 BHN |

| Melting Point | 1450 °C |

| Thermal Conductivity | 24 W/mK |

| Heat Capacity | 460 J/g K |

| Price | 5 $/kg |

Density of Martensitic Stainless Steel

Typical densities of various substances are at atmospheric pressure. Density is defined as the mass per unit volume. It is an intensive property, which is mathematically defined as mass divided by volume: ρ = m/V

In words, the density (ρ) of a substance is the total mass (m) of that substance divided by the total volume (V) occupied by that substance. The standard SI unit is kilograms per cubic meter (kg/m3). The Standard English unit is pounds mass per cubic foot (lbm/ft3).

Density of Martensitic Stainless Steel is 7650 kg/m3.

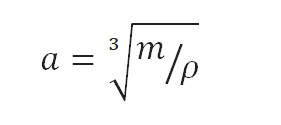

Example: Density

Calculate the height of a cube made of Martensitic Stainless Steel, which weighs one metric ton.

Solution:

Density is defined as the mass per unit volume. It is mathematically defined as mass divided by volume: ρ = m/V

As the volume of a cube is the third power of its sides (V = a3), the height of this cube can be calculated:

The height of this cube is then a = 0.508 m.

Density of Materials

Mechanical Properties of Martensitic Stainless Steel

Strength of Martensitic Stainless Steel

In mechanics of materials, the strength of a material is its ability to withstand an applied load without failure or plastic deformation. Strength of materials basically considers the relationship between the external loads applied to a material and the resulting deformation or change in material dimensions. Strength of a material is its ability to withstand this applied load without failure or plastic deformation.

Ultimate Tensile Strength

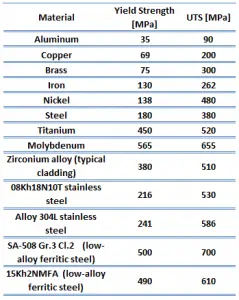

Ultimate tensile strength of Martensitic Stainless Steel – Grade 440C is 760 MPa.

The ultimate tensile strength is the maximum on the engineering stress-strain curve. This corresponds to the maximum stress that can be sustained by a structure in tension. Ultimate tensile strength is often shortened to “tensile strength” or even to “the ultimate.” If this stress is applied and maintained, fracture will result. Often, this value is significantly more than the yield stress (as much as 50 to 60 percent more than the yield for some types of metals). When a ductile material reaches its ultimate strength, it experiences necking where the cross-sectional area reduces locally. The stress-strain curve contains no higher stress than the ultimate strength. Even though deformations can continue to increase, the stress usually decreases after the ultimate strength has been achieved. It is an intensive property; therefore its value does not depend on the size of the test specimen. However, it is dependent on other factors, such as the preparation of the specimen, the presence or otherwise of surface defects, and the temperature of the test environment and material. Ultimate tensile strengths vary from 50 MPa for an aluminum to as high as 3000 MPa for very high-strength steels.

The ultimate tensile strength is the maximum on the engineering stress-strain curve. This corresponds to the maximum stress that can be sustained by a structure in tension. Ultimate tensile strength is often shortened to “tensile strength” or even to “the ultimate.” If this stress is applied and maintained, fracture will result. Often, this value is significantly more than the yield stress (as much as 50 to 60 percent more than the yield for some types of metals). When a ductile material reaches its ultimate strength, it experiences necking where the cross-sectional area reduces locally. The stress-strain curve contains no higher stress than the ultimate strength. Even though deformations can continue to increase, the stress usually decreases after the ultimate strength has been achieved. It is an intensive property; therefore its value does not depend on the size of the test specimen. However, it is dependent on other factors, such as the preparation of the specimen, the presence or otherwise of surface defects, and the temperature of the test environment and material. Ultimate tensile strengths vary from 50 MPa for an aluminum to as high as 3000 MPa for very high-strength steels.

Yield Strength

Yield strength of Martensitic Stainless Steel – Grade 440C is 450 MPa.

The yield point is the point on a stress-strain curve that indicates the limit of elastic behavior and the beginning plastic behavior. Yield strength or yield stress is the material property defined as the stress at which a material begins to deform plastically whereas yield point is the point where nonlinear (elastic + plastic) deformation begins. Prior to the yield point, the material will deform elastically and will return to its original shape when the applied stress is removed. Once the yield point is passed, some fraction of the deformation will be permanent and non-reversible. Some steels and other materials exhibit a behaviour termed a yield point phenomenon. Yield strengths vary from 35 MPa for a low-strength aluminum to greater than 1400 MPa for very high-strength steels.

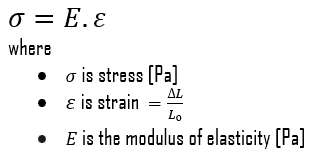

Young’s Modulus of Elasticity

Young’s modulus of elasticity of Martensitic Stainless Steel – Grade 440C is 200 GPa.

The Young’s modulus of elasticity is the elastic modulus for tensile and compressive stress in the linear elasticity regime of a uniaxial deformation and is usually assessed by tensile tests. Up to a limiting stress, a body will be able to recover its dimensions on removal of the load. The applied stresses cause the atoms in a crystal to move from their equilibrium position. All the atoms are displaced the same amount and still maintain their relative geometry. When the stresses are removed, all the atoms return to their original positions and no permanent deformation occurs. According to the Hooke’s law, the stress is proportional to the strain (in the elastic region), and the slope is Young’s modulus. Young’s modulus is equal to the longitudinal stress divided by the strain.

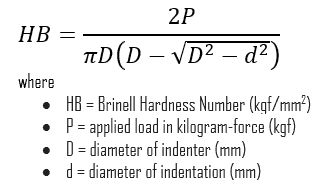

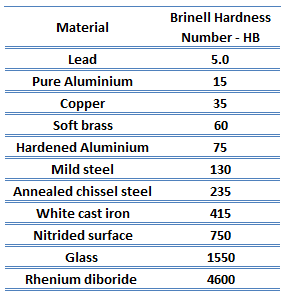

Hardness of Martensitic Stainless Steel

Brinell hardness of Martensitic Stainless Steel – Grade 440C is approximately 270 MPa.

In materials science, hardness is the ability to withstand surface indentation (localized plastic deformation) and scratching. Hardness is probably the most poorly defined material property because it may indicate resistance to scratching, resistance to abrasion, resistance to indentation or even resistance to shaping or localized plastic deformation. Hardness is important from an engineering standpoint because resistance to wear by either friction or erosion by steam, oil, and water generally increases with hardness.

In materials science, hardness is the ability to withstand surface indentation (localized plastic deformation) and scratching. Hardness is probably the most poorly defined material property because it may indicate resistance to scratching, resistance to abrasion, resistance to indentation or even resistance to shaping or localized plastic deformation. Hardness is important from an engineering standpoint because resistance to wear by either friction or erosion by steam, oil, and water generally increases with hardness.

Brinell hardness test is one of indentation hardness tests, that has been developed for hardness testing. In Brinell tests, a hard, spherical indenter is forced under a specific load into the surface of the metal to be tested. The typical test uses a 10 mm (0.39 in) diameter hardened steel ball as an indenter with a 3,000 kgf (29.42 kN; 6,614 lbf) force. The load is maintained constant for a specified time (between 10 and 30 s). For softer materials, a smaller force is used; for harder materials, a tungsten carbide ball is substituted for the steel ball.

The test provides numerical results to quantify the hardness of a material, which is expressed by the Brinell hardness number – HB. The Brinell hardness number is designated by the most commonly used test standards (ASTM E10-14[2] and ISO 6506–1:2005) as HBW (H from hardness, B from brinell and W from the material of the indenter, tungsten (wolfram) carbide). In former standards HB or HBS were used to refer to measurements made with steel indenters.

The Brinell hardness number (HB) is the load divided by the surface area of the indentation. The diameter of the impression is measured with a microscope with a superimposed scale. The Brinell hardness number is computed from the equation:

There are a variety of test methods in common use (e.g. Brinell, Knoop, Vickers and Rockwell). There are tables that are available correlating the hardness numbers from the different test methods where correlation is applicable. In all scales, a high hardness number represents a hard metal.

Example: Strength

Assume a plastic rod, which is made of Martensitic Stainless Steel. This plastic rod has a cross-sectional area of 1 cm2. Calculate the tensile force needed to achieve the ultimate tensile strength for this material, which is: UTS = 760 MPa.

Solution:

Stress (σ) can be equated to the load per unit area or the force (F) applied per cross-sectional area (A) perpendicular to the force as:

therefore, the tensile force needed to achieve the ultimate tensile strength is:

F = UTS x A = 760 x 106 x 0.0001 = 76 000 N

Thermal Properties of Martensitic Stainless Steel

Thermal properties of materials refer to the response of materials to changes in their thermodynamics/thermodynamic-properties/what-is-temperature-physics/”>temperature and to the application of heat. As a solid absorbs thermodynamics/what-is-energy-physics/”>energy in the form of heat, its temperature rises and its dimensions increase. But different materials react to the application of heat differently.

Heat capacity, thermal expansion, and thermal conductivity are properties that are often critical in the practical use of solids.

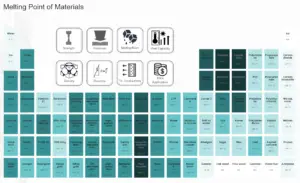

Melting Point of Martensitic Stainless Steel

Melting point of Martensitic Stainless Steel – Grade 440C steel is around 1450°C.

In general, melting is a phase change of a substance from the solid to the liquid phase. The melting point of a substance is the temperature at which this phase change occurs. The melting point also defines a condition in which the solid and liquid can exist in equilibrium.

Thermal Conductivity of Martensitic Stainless Steel

The thermal conductivity of Martensitic Stainless Steel – Grade 440C is 24 W/(m.K).

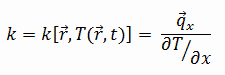

The heat transfer characteristics of a solid material are measured by a property called the thermal conductivity, k (or λ), measured in W/m.K. It is a measure of a substance’s ability to transfer heat through a material by conduction. Note that Fourier’s law applies for all matter, regardless of its state (solid, liquid, or gas), therefore, it is also defined for liquids and gases.

The thermal conductivity of most liquids and solids varies with temperature. For vapors, it also depends upon pressure. In general:

Most materials are very nearly homogeneous, therefore we can usually write k = k (T). Similar definitions are associated with thermal conductivities in the y- and z-directions (ky, kz), but for an isotropic material the thermal conductivity is independent of the direction of transfer, kx = ky = kz = k.

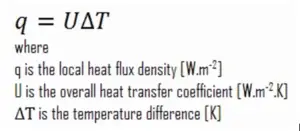

Example: Heat transfer calculation

Thermal conductivity is defined as the amount of heat (in watts) transferred through a square area of material of given thickness (in metres) due to a difference in temperature. The lower the thermal conductivity of the material the greater the material’s ability to resist heat transfer.

Thermal conductivity is defined as the amount of heat (in watts) transferred through a square area of material of given thickness (in metres) due to a difference in temperature. The lower the thermal conductivity of the material the greater the material’s ability to resist heat transfer.

Calculate the rate of heat flux through a wall 3 m x 10 m in area (A = 30 m2). The wall is 15 cm thick (L1) and it is made of Martensitic Stainless Steel with the thermal conductivity of k1 = 24 W/m.K (poor thermal insulator). Assume that, the indoor and the outdoor temperatures are 22°C and -8°C, and the convection heat transfer coefficients on the inner and the outer sides are h1 = 10 W/m2K and h2 = 30 W/m2K, respectively. Note that, these convection coefficients strongly depend especially on ambient and interior conditions (wind, humidity, etc.).

Calculate the heat flux (heat loss) through this wall.

Solution:

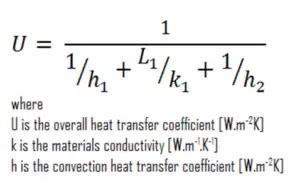

As was written, many of the heat transfer processes involve composite systems and even involve a combination of both conduction and convection. With these composite systems, it is often convenient to work with an overall heat transfer coefficient, known as a U-factor. The U-factor is defined by an expression analogous to Newton’s law of cooling:

The overall heat transfer coefficient is related to the total thermal resistance and depends on the geometry of the problem.

Assuming one-dimensional heat transfer through the plane wall and disregarding radiation, the overall heat transfer coefficient can be calculated as:

The overall heat transfer coefficient is then: U = 1 / (1/10 + 0.15/24 + 1/30) = 7.16 W/m2K

The heat flux can be then calculated simply as: q = 7.16 [W/m2K] x 30 [K] = 214.93 W/m2

The total heat loss through this wall will be: qloss = q . A = 214.93 [W/m2] x 30 [m2] = 6447.76 W