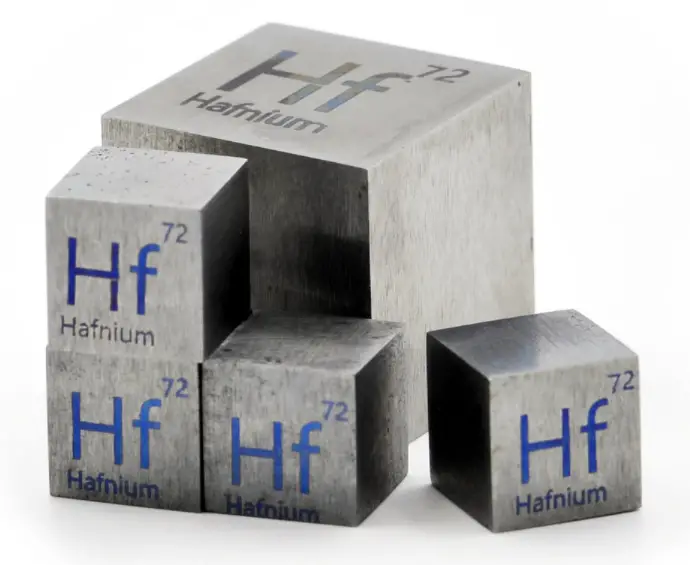

About Hafnium

Hafnium is a lustrous, silvery gray, tetravalent transition metal, hafnium chemically resembles zirconium and is found in many zirconium minerals. Hafnium’s large neutron capture cross-section makes it a good material for neutron absorption in control rods in nuclear power plants, but at the same time requires that it be removed from the neutron-transparent corrosion-resistant zirconium alloys used in nuclear reactors.

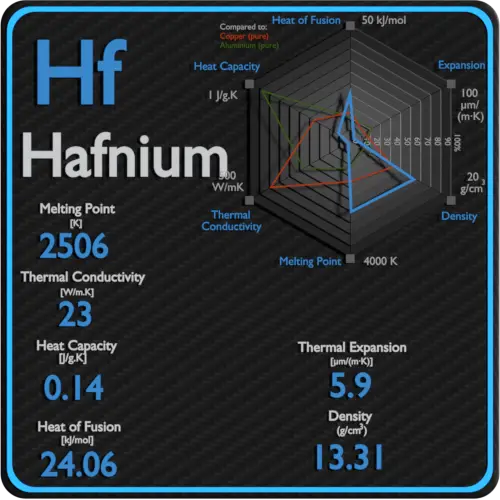

Thermal Properties of Hafnium

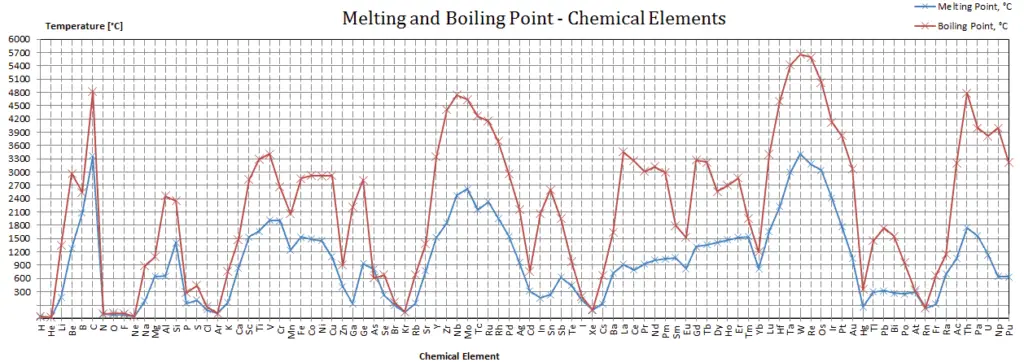

Hafnium – Melting Point and Boiling Point

Melting point of Hafnium is 2227°C.

Boiling point of Hafnium is 4600°C.

Note that, these points are associated with the standard atmospheric pressure.

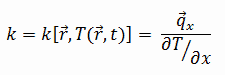

Hafnium – Thermal Conductivity

Thermal conductivity of Hafnium is 23 W/(m·K).

The heat transfer characteristics of a solid material are measured by a property called the thermal conductivity, k (or λ), measured in W/m.K. It is a measure of a substance’s ability to transfer heat through a material by conduction. Note that Fourier’s law applies for all matter, regardless of its state (solid, liquid, or gas), therefore, it is also defined for liquids and gases.

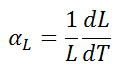

Coefficient of Thermal Expansion of Hafnium

Linear thermal expansion coefficient of Hafnium is 5.9 µm/(m·K)

Thermal expansion is generally the tendency of matter to change its dimensions in response to a change in temperature. It is usually expressed as a fractional change in length or volume per unit temperature change.

See also: Mechanical Properties of Hafnium

Boiling Point

In general, boiling is a phase change of a substance from the liquid to the gas phase. The boiling point of a substance is the temperature at which this phase change (boiling or vaporization) occurs. The temperature at which vaporization (boiling) starts to occur for a given pressure is also known as the saturation temperature and at this conditions a mixture of vapor and liquid can exist together. The liquid can be said to be saturated with thermal energy. Any addition of thermal energy results in a phase transition. At the boiling point the two phases of a substance, liquid and vapor, have identical free energies and therefore are equally likely to exist. Below the boiling point, the liquid is the more stable state of the two, whereas above the gaseous form is preferred. The pressure at which vaporization (boiling) starts to occur for a given temperature is called the saturation pressure. When considered as the temperature of the reverse change from vapor to liquid, it is referred to as the condensation point.

As can be seen, the boiling point of a liquid varies depending upon the surrounding environmental pressure. A liquid in a partial vacuum has a lower boiling point than when that liquid is at atmospheric pressure. A liquid at high pressure has a higher boiling point than when that liquid is at atmospheric pressure. For example, water boils at 100°C (212°F) at sea level, but at 93.4°C (200.1°F) at 1900 metres (6,233 ft) altitude. On the other hand, water boils at 350°C (662°F) at 16.5 MPa (typical pressure of PWRs).

In the periodic table of elements, the element with the lowest boiling point is helium. Both the boiling points of rhenium and tungsten exceed 5000 K at standard pressure. Since it is difficult to measure extreme temperatures precisely without bias, both have been cited in the literature as having the higher boiling point.

Melting Point

In general, melting is a phase change of a substance from the solid to the liquid phase. The melting point of a substance is the temperature at which this phase change occurs. The melting point also defines a condition in which the solid and liquid can exist in equilibrium. Adding a heat will convert the solid into a liquid with no temperature change. At the melting point the two phases of a substance, liquid and vapor, have identical free energies and therefore are equally likely to exist. Below the melting point, the solid is the more stable state of the two, whereas above the liquid form is preferred. The melting point of a substance depends on pressure and is usually specified at standard pressure. When considered as the temperature of the reverse change from liquid to solid, it is referred to as the freezing point or crystallization point.

See also: Melting Point Depression

The first theory explaining mechanism of melting in the bulk was proposed by Lindemann, who used vibration of atoms in the crystal to explain the melting transition. Solids are similar to liquids in that both are condensed states, with particles that are far closer together than those of a gas. The atoms in a solid are tightly bound to each other, either in a regular geometric lattice (crystalline solids, which include metals and ordinary ice) or irregularly (an amorphous solid such as common window glass), and are typically low in energy. The motion of individual atoms, ions, or molecules in a solid is restricted to vibrational motion about a fixed point. As a solid is heated, its particles vibrate more rapidly as the solid absorbs kinetic energy. At some point the amplitude of vibration becomes so large that the atoms start to invade the space of their nearest neighbors and disturb them and the melting process initiates. The melting point is the temperature at which the disruptive vibrations of the particles of the solid overcome the attractive forces operating within the solid.

As with boiling points, the melting point of a solid is dependent on the strength of those attractive forces. For example, sodium chloride (NaCl) is an ionic compound that consists of a multitude of strong ionic bonds. Sodium chloride melts at 801°C. On the other hand, ice (solid H2O) is a molecular compound whose molecules are held together by hydrogen bonds, which is effectively a strong example of an interaction between two permanent dipoles. Though hydrogen bonds are the strongest of the intermolecular forces, the strength of hydrogen bonds is much less than that of ionic bonds. The melting point of ice is 0 °C.

Covalent bonds often result in the formation of small collections of better-connected atoms called molecules, which in solids and liquids are bound to other molecules by forces that are often much weaker than the covalent bonds that hold the molecules internally together. Such weak intermolecular bonds give organic molecular substances, such as waxes and oils, their soft bulk character, and their low melting points (in liquids, molecules must cease most structured or oriented contact with each other).

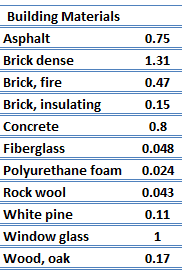

The heat transfer characteristics of a solid material are measured by a property called the thermal conductivity, k (or λ), measured in W/m.K. It is a measure of a substance’s ability to transfer heat through a material by conduction. Note that Fourier’s law applies for all matter, regardless of its state (solid, liquid, or gas), therefore, it is also defined for liquids and gases.

The thermal conductivity of most liquids and solids varies with temperature. For vapors, it also depends upon pressure. In general:

Most materials are very nearly homogeneous, therefore we can usually write k = k (T). Similar definitions are associated with thermal conductivities in the y- and z-directions (ky, kz), but for an isotropic material the thermal conductivity is independent of the direction of transfer, kx = ky = kz = k.

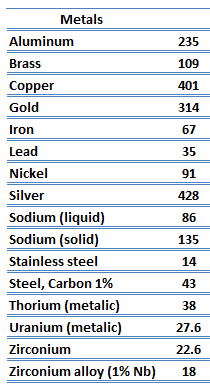

Thermal Conductivity of Metals

- the migration of free electrons

- lattice vibrational waves (phonons)

When electrons and phonons carry thermal energy leading to conduction heat transfer in a solid, the thermal conductivity may be expressed as:

k = ke + kph

Metals are solids and as such they possess crystalline structure where the ions (nuclei with their surrounding shells of core electrons) occupy translationally equivalent positions in the crystal lattice. Metals in general have high electrical conductivity, high thermal conductivity, and high density. Accordingly, transport of thermal energy may be due to two effects:

Metals are solids and as such they possess crystalline structure where the ions (nuclei with their surrounding shells of core electrons) occupy translationally equivalent positions in the crystal lattice. Metals in general have high electrical conductivity, high thermal conductivity, and high density. Accordingly, transport of thermal energy may be due to two effects:

- the migration of free electrons

- lattice vibrational waves (phonons).

When electrons and phonons carry thermal energy leading to conduction heat transfer in a solid, the thermal conductivity may be expressed as:

k = ke + kph

The unique feature of metals as far as their structure is concerned is the presence of charge carriers, specifically electrons. The electrical and thermal conductivities of metals originate from the fact that their outer electrons are delocalized. Their contribution to the thermal conductivity is referred to as the electronic thermal conductivity, ke. In fact, in pure metals such as gold, silver, copper, and aluminum, the heat current associated with the flow of electrons by far exceeds a small contribution due to the flow of phonons. In contrast, for alloys, the contribution of kph to k is no longer negligible.

Thermal Conductivity of Nonmetals

For nonmetallic solids, k is determined primarily by kph, which increases as the frequency of interactions between the atoms and the lattice decreases. In fact, lattice thermal conduction is the dominant thermal conduction mechanism in nonmetals, if not the only one. In solids, atoms vibrate about their equilibrium positions (crystal lattice). The vibrations of atoms are not independent of each other, but are rather strongly coupled with neighboring atoms. The regularity of the lattice arrangement has an important effect on kph, with crystalline (well-ordered) materials like quartz having a higher thermal conductivity than amorphous materials like glass. At sufficiently high temperatures kph ∝ 1/T.

For nonmetallic solids, k is determined primarily by kph, which increases as the frequency of interactions between the atoms and the lattice decreases. In fact, lattice thermal conduction is the dominant thermal conduction mechanism in nonmetals, if not the only one. In solids, atoms vibrate about their equilibrium positions (crystal lattice). The vibrations of atoms are not independent of each other, but are rather strongly coupled with neighboring atoms. The regularity of the lattice arrangement has an important effect on kph, with crystalline (well-ordered) materials like quartz having a higher thermal conductivity than amorphous materials like glass. At sufficiently high temperatures kph ∝ 1/T.

The quanta of the crystal vibrational field are referred to as ‘‘phonons.’’ A phonon is a collective excitation in a periodic, elastic arrangement of atoms or molecules in condensed matter, like solids and some liquids. Phonons play a major role in many of the physical properties of condensed matter, like thermal conductivity and electrical conductivity. In fact, for crystalline, nonmetallic solids such as diamond, kph can be quite large, exceeding values of k associated with good conductors, such as aluminum. In particular, diamond has the highest hardness and thermal conductivity (k = 1000 W/m.K) of any bulk material.

Thermal Conductivity of Liquids and Gases

In physics, a fluid is a substance that continually deforms (flows) under an applied shear stress. Fluids are a subset of the phases of matter and include liquids, gases, plasmas and, to some extent, plastic solids. Because the intermolecular spacing is much larger and the motion of the molecules is more random for the fluid state than for the solid state, thermal energy transport is less effective. The thermal conductivity of gases and liquids is therefore generally smaller than that of solids. In liquids, the thermal conduction is caused by atomic or molecular diffusion. In gases, the thermal conduction is caused by diffusion of molecules from higher energy level to the lower level.

Thermal Conductivity of Gases

The effect of temperature, pressure, and chemical species on the thermal conductivity of a gas may be explained in terms of the kinetic theory of gases. Air and other gases are generally good insulators, in the absence of convection. Therefore, many insulating materials (e.g.polystyrene) function simply by having a large number of gas-filled pockets which prevent large-scale convection. Alternation of gas pocket and solid material causes that the heat must be transferred through many interfaces causing rapid decrease in heat transfer coefficient.

The effect of temperature, pressure, and chemical species on the thermal conductivity of a gas may be explained in terms of the kinetic theory of gases. Air and other gases are generally good insulators, in the absence of convection. Therefore, many insulating materials (e.g.polystyrene) function simply by having a large number of gas-filled pockets which prevent large-scale convection. Alternation of gas pocket and solid material causes that the heat must be transferred through many interfaces causing rapid decrease in heat transfer coefficient.

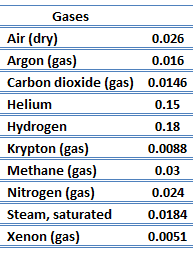

The thermal conductivity of gases is directly proportional to the density of the gas, the mean molecular speed, and especially to the mean free path of molecule. The mean free path also depends on the diameter of the molecule, with larger molecules more likely to experience collisions than small molecules, which is the average distance traveled by an energy carrier (a molecule) before experiencing a collision. Light gases, such as hydrogen and helium typically have high thermal conductivity. Dense gases such as xenon and dichlorodifluoromethane have low thermal conductivity.

In general, the thermal conductivity of gases increases with increasing temperature.

Thermal Conductivity of Liquids

As was written, in liquids, the thermal conduction is caused by atomic or molecular diffusion, but physical mechanisms for explaining the thermal conductivity of liquids are not well understood. Liquids tend to have better thermal conductivity than gases, and the ability to flow makes a liquid suitable for removing excess heat from mechanical components. The heat can be removed by channeling the liquid through a heat exchanger. The coolants used in nuclear reactors include water or liquid metals, such as sodium or lead.

The thermal conductivity of nonmetallic liquids generally decreases with increasing temperature.

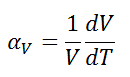

Thermal expansion is generally the tendency of matter to change its dimensions in response to a change in temperature. It is usually expressed as a fractional change in length or volume per unit temperature change. Thermal expansion is common for solids, liquids and for gases. Unlike gases or liquids, solid materials tend to keep their shape when undergoing thermal expansion. A linear expansion coefficient is usually employed in describing the expansion of a solid, while a volume expansion coefficient is more useful for a liquid or a gas.

The linear thermal expansion coefficient is defined as:

where L is a particular length measurement and dL/dT is the rate of change of that linear dimension per unit change in temperature.

The volumetric thermal expansion coefficient is the most basic thermal expansion coefficient, and the most relevant for fluids. In general, substances expand or contract when their temperature changes, with expansion or contraction occurring in all directions.

The volumetric thermal expansion coefficient is defined as:

where L is the volume of the material and dV/dT is the rate of change of that volume per unit change in temperature.

In a solid or liquid, there is a dynamic balance between the cohesive forces holding the atoms or molecules together and the conditions created by temperature. Therefore higher temperatures imply greater distance between atoms. Different materials have different bonding forces and therefore different expansion coefficients. If a crystalline solid is isometric (has the same structural configuration throughout), the expansion will be uniform in all dimensions of the crystal. For these materials, the area and volumetric thermal expansion coefficient are, respectively, approximately twice and three times larger than the linear thermal expansion coefficient (αV = 3αL). If it is not isometric, there may be different expansion coefficients for different crystallographic directions, and the crystal will change shape as the temperature changes.

Summary

| Element | Hafnium |

| Melting Point | 2227 °C |

| Boiling Point | 4600 °C |

| Thermal Conductivity | 23 W/mK |

| Thermal Expansion Coefficient | 5.9 µm/mK |

| Density | 13.31 g/cm3 |

Source: www.luciteria.com